Against Negative Partisanship

There's no room for greater goods with political outlooks that perpetually enable lesser evils.

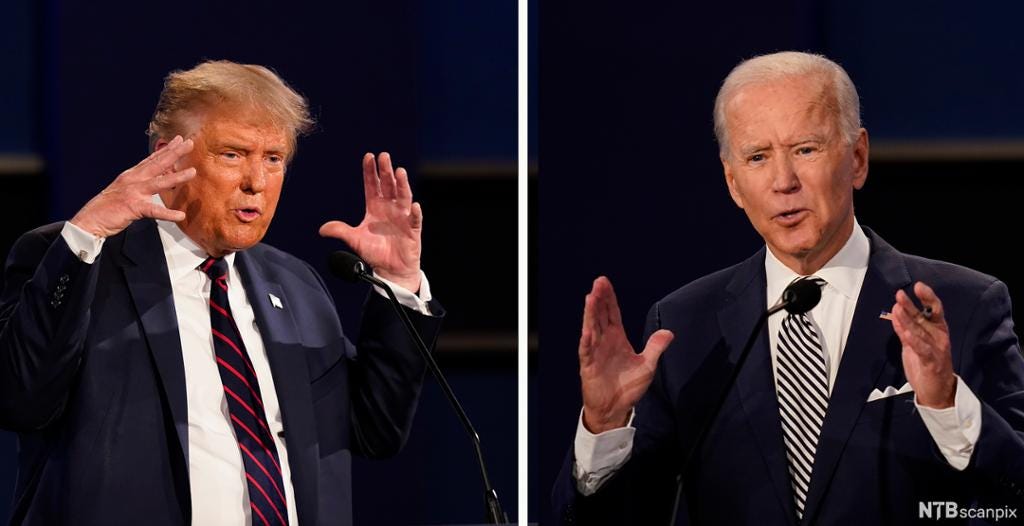

Recently, an organization called No Labels has been making headlines with its efforts to secure ballot spots for an independent presidential alternative should the two major parties again attempt to force America to choose between Joe Biden and Donald Trump. Responses from dedicated partisans both to the Left and to the Right have been predictable, but there has been an eruption of debate over this effort among non-Trump conservatives and right-leaning moderates over the prudence of this endeavor.

For many non-Trump conservatives, such as myself, there is no possible scenario in which they will vote for Joe Biden. We didn’t pull the lever for him in 2020, even when he was campaigning as a “return to normal” moderate Democrat, because we correctly predicted that he was nothing of the sort. After four years of observing just how right we were to question his rhetoric and promises, voting for him and an extreme progressive mandate is simply beyond what we can stomach.

But for others, such as Nick Catoggio over at the Dispatch, the concern is that any serious alternative effort to the two major parties in 2024 will accomplish little more than a spoiler effect that could throw the election to Donald Trump. Catoggio goes so far as to say, “It’s so clear that a centrist third-party candidate would hurt the party that isn’t a cult while helping the one that is that we’re left to wonder whether No Labels is quietly in the tank for Trump.”

In defense of this declaration, Catoggio offers a well-written, well-considered piece that cites thought-provoking statistics and analysis supporting his argument. But at the end of the day, what he’s offering is yet another lesser-of-two-evils, negative partisanship screed that offers a path forward not substantively different than the famous Flight 93 Election manifesto that convinced so many Republicans in 2016 to hold their nose and vote for Donald Trump.

Michael Anton’s article in the Claremont Review of Books is surprisingly more articulate than many give it credit, but the argument boils down to a sophisticated yet misguided lesser-of-two-evils justification, as evidenced by perhaps its most famous line where Anton asserts that “a Hillary Clinton presidency is Russian Roulette with a semi-auto. With Trump, at least you can spin the cylinder and take your chances.”

In their belief that presidential elections in the current political climate present existential questions, Catoggio and Anton agree. In their view that neither party is presenting the best or the most preferable candidates, Catoggio and Anton agree. Where they disagree is which party represents the most salient and immediate threat and which party is concerning but presents problems that can be lived with.

The problem with their approaches is that it inevitably creates an insurmountable divide. The first, and often only, political question for folks like Catoggio and Anton is who is worse. If you think someone like Hillary Clinton or Joe Biden would be the end of the American Republic, you will vote for whoever the Republicans put forth. If you believe a second term for Donald Trump would end democracy in America, you will vote for whoever the Democrats send your way. The political debate functionally ends there.

In such an environment of runaway negative partisanship, the system as intended simply cannot work. If the only political question we ask is “Who is worse?” then we have removed the incentives for the political parties to put forward candidates capable of achieving majority support on their own merits. This is quite literally a race to the bottom, a twisted game of political leapfrog into further dysfunction.

In an era where two perpetually dysfunctional political parties consistently give us lesser evils rather than greater goods, those who recognize and are dissatisfied with these subpar offerings must find a better way. Otherwise, we are little more than cogs in the ongoing dysfunction. What incentive do the political parties have to offer us greater goods if the fears of negative partisanship are sufficient to convince us to support lesser evils?

I, more than most, appreciate the virtue of prudence. On more than one occasion, I have defended the American two-party system. I’m a member of the Republican Party. I believe strongly in working within the existing system rather than simply shouting my disdain from the wilderness.

From a very early age, I subscribed to the view offered by Hugh B. Brown, a former leader of my church (I’m a Latter-day Saint):

“I have found through long experience that our two-party system is sound. Beware of those who are so lacking in humility that they cannot come within the framework of one of our two great parties. Our nation has avoided chaos...because men have been able to temper their own desires sufficiently to seek broad agreement within one of the two major parties, rather than forming splinter groups around one radical idea. Our two-party system has served us well and should not be lightly discarded.”

My current belief is that everyone right-of-center should be engaging within the Republican Party in support of whichever non-Trump alternative that best reflects their values and principles (If someone’s values and principles disallow them from engaging within the GOP, then they should register Democrat and engage within that political party to bend it toward true moderation). My focus at the present point in time is on the primary process, and I remain optimistic that by the time the actual contests roll around, Republican voters will have ample opportunity to choose another path than the one the party is currently on.

As for the No Labels effort, I view it as a fail-safe should efforts to defeat Donald Trump in the Republican Primary fail. At first glance, this may seem imprudent and against my stated belief that one should work within the existing two-party structure whenever possible.

But this principle of prudence is heavily conditional on the healthy function of political institutions. The aforementioned Hugh B. Brown quote has several key elements that traditionally have defined the strength of the two-party system. Particularly, it is that the system encourages individuals to temper their desires and work within a framework that creates broad agreement.

Our two major parties, when functioning properly, perform as moderating institutions in our political system. A two-party system necessitates a goal in each party to achieve majority support from the electorate. When healthy, a party that finds itself bleeding support will adjust its strategies, even alter its vision, and will take great pains to put forward different and new offerings for public office who can change the trajectory of party popularity and success.

If one or the other party becomes captured by an extreme element, the other party would adjust to absorb abandoned constituencies as it continuously sought a broader coalition. This would serve to marginalize the extreme element of the captured party, which would then be overthrown by moderating elements seeking to reassert viability and relevance.

But this is not how our two parties tend to operate today. Instead, the moderating influences of both major parties have simultaneously grown weak, creating a dual dysfunctional scenario where both have been captured by extreme elements simultaneously. Instead of adjusting to absorb abandoned constituencies, both parties play off of each other’s excesses and reject any form of moderation as a surrender to their opponents.

In this new scenario, each year and each election create broader and wider gulfs between the parties. More and more Americans find no easy home in either party but are forced to choose which party presents the least worst alternative, feeling they have no other choice but to embrace a “lesser of two evils” approach.

But, of course, politicians don’t run for office because they see themselves as lesser evils. They run for office because they think of themselves as greater goods, even when they’re nothing of the sort (especially so, it seems). Regardless of our genuine reasons for voting one way or the other, the victor always interprets their victory as a powerful mandate. They push the needle further, their political opponents respond with even more hysterical rhetoric, and the cycle of institutional decay, control of the parties by extreme elements, and marginal drift away from healthy moderation continues.

In normal times and with healthy political institutions, the prudent approach is indeed the proper path. This is why I work so hard to encourage participation within the parties and to encourage those who are unhappy with the current offerings to roll up their sleeves and help create constituencies for better choices within the existing parties (advice, by the way, that many of the lesser-of-two-evils types not only reject but disdain). I am greatly motivated to reassert normal times and reinvigorate healthy political institutions.

But when circumstances are not normal, when the parties are blindingly dysfunctional, and when the choices offered to the nation by the parties are simply unacceptable, what would normally be the prudent approach instead feeds the very problem the two-party system traditionally avoided. While choosing the best of two alternatives encourages moderation in healthy political parties, choosing the least worst of two alternatives enables extremism in dysfunctional political parties.

When both parties simultaneously become captured by extreme elements, the only prudent choice remaining is to simultaneously reject them. New institutions and efforts must arise, operating on the traditional principles of moderation, or the two parties must at least be robbed of the mandate that feeds the dysfunction by forcing them to win with only a small plurality of votes, weakening their authority and legitimacy until they are forced back into healthy moderation and proper coalitional efforts.

It is not prudent to allow unacceptable candidates to take entire blocks of voters for granted because they know they will vote against the alternative. This surrenders power and influence. It enables a process that results in the misrepresentation of the values and beliefs of the American people in the halls of government.

If the republic is in danger, it will not be saved by deciding which party is the least worst political institution. It will be saved by breaking the cycle of dual dysfunction and rebuilding the two-party system as it should operate within the existing parties when possible and from without with new, innovative institutions when necessary.

There are over 330 million Americans. Somewhere, there are the philosophical, ethical, and intellectual equivalents of the best and brightest this country has ever had to offer. The political parties are not currently seeking them out and putting them on the ballot.

That should be unacceptable.

I like the use of “non-Trump” as opposed to Never Trump in order to distinguish principled conservatives who refuse to support Trump and oppose him, but also don’t become Democrats.

If Donald Trump becomes president, there will be no boundaries to his revenge. He is pure evil. I would vote for a ham sandwich with mayonnaise before I vote for Trump. I detest mayonnaise.