Cato and Eternal Principles

It's important to remember that truth endures, and lasting legacies result more from holding to our principles than sacrificing them to a sense of apocalyptic doom.

In many ways, the American Republic was a resurrection of the Roman Republic. The founders embraced this idea. That’s why they named the upper chamber of Congress after the Roman Senate. That’s why so many of our government buildings and landmarks are so obviously designed using Roman architectural inspiration. It’s why we put Latin on our coinage and use Latin terms and mottos throughout government, the arts, and education.

Consider, for a moment, that the Roman Republic ended before the birth of Christ. Yet, a group of people on a different continent and with no ethnic or national connection to the ancient Romans chose to build their new nation with ideas and trappings of a representative government that existed nearly two centuries before it.

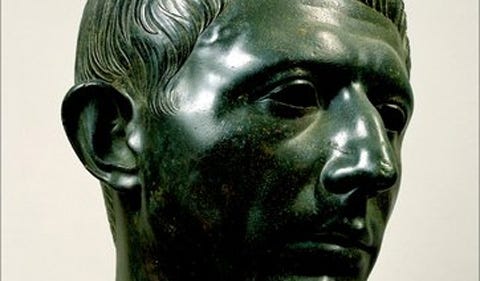

This amazing and astounding reality often makes me think of Cato the Younger. He was a Roman politician and leader who chose to die by his own hand along with the Roman Republic rather than submit to Caesar and live in a world where his nation had become an empire.

Historians consider Cato’s final act to be a last act of defiance against Caesar and his usurped authority. By taking his own life, Cato assured that Caesar couldn’t pardon him for his resistance. He declared with his death that he saw no legitimacy in the reign of an emperor.

Despite Cato’s defeat in his efforts to maintain the Roman Republic, many Romans remembered his final defiance, preserving his memory beyond even the fall of the Roman Empire. Cato’s memory was strong enough for him to make it into Dante’s The Divine Comedy. He was a figure of reverence during the enlightenment. One of George Washington’s favorite plays was Joseph Addison’s Cato, a Tragedy.

Here’s my point: the truths and republican notions of Cato the Younger survived beyond the Roman Republic and beyond the fall of Rome many years later because they were universal truths. They were not merely pure Roman precepts applicable only within the context of Roman Nationalism.

I don’t know whether Cato foresaw the final fall of the Roman Republic. Still, I tend to believe his first love was his principles, and it was to his principles he wished to leave a legacy. That his principles live on in America, with no connection to Rome beyond a philosophical one, would not be considered a failure to him but a final triumph.

No matter where the political winds take us and our country, our first loyalty must be to our principles. Whether the American nation lives on for hundreds of more years or ends tomorrow, it will be the untarnished principles of those who know what they stand for and refuse to submit to the pressures of the mob, the academy, or the veritable powers-that-be who will leave a lasting legacy.

Well put. The post-liberal critics of the American Founders would do well to actually read a few Founders - the Roman Republic was more influential on them than Modern (meaning after Machiavelli) Rationalists.

I’ve long been fond of Roman history and there is much to love in the Republican period for all its many flaws. Rome had perhaps republicanism without liberalism, and it was a highly unequal and very aristocratic society. But compared to all who came before them (save perhaps the Greeks) and many who would come after (at least for fifteen-hundred years), the Roman Republic represented a stunning achievement in human freedom and flourishing. They grasped at something and though they fall very far short of perfection, they knew they had something good.

Cato is one of the best examples of Roman virtus. I’m also of the opinion that Brutus and Cassius were patriots. I’m taken with Tacitus’ description of them. Writing much later, he seemed to really understand as few others did just how far Rome had fallen, and what they had really lost. He knew there was something worth preserving in the Roman Republic and he seemed impressed by the tragedy for the human race that was its fall. If you haven’t read his account of the early imperial period, I highly recommend it.