Conservatism and Immutable Verities

The core of conservatism, or of any political philosophy, is the absolute conviction that there are immutable verities.

A credible argument can be made that the quest for a unified field theory by which to organize a society conducive to human happiness is a fool’s errand. Angels-on-the-head-of-a-pin justifications for exclusion beset us from the moment we begin such an attempt.

Consider the variety of figures, organizations, journals, and movements to which people apply the term “conservative.” There’s variety between them, but not much within them anymore. While champions of different points of emphasis have always been tempted to put forth purity tests, others have concurrently looked for ways to fashion them into a coherent whole.

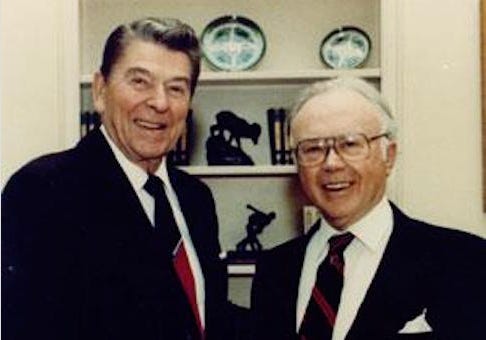

The best-known of these projects is the Three-Legged Stool. Ronald Reagan coined the term, but he derived it from ideas articulated by Frank S. Meyer, one of the founding editors of National Review, often termed fusionism. The shorthand characterization of the three legs is social conservatism, free-market economics, and a foreign policy based on vigilant resistance to totalitarianism.

Russell Kirk’s attempt at bullet-point distillation of the conservative vision took the form of what he called six canons. They set transcendence, human awe at that transcendence, unavoidable “inequality of condition,” property’s essential link to freedom, wariness of novel prescriptions for societal betterment, and a prudent reaction to inevitable change as its must-have aspects.

While such positive formulations have served as dependable guides, conservatism arose in reaction to forces that, in stages, have been changing the face of Western civilization for several centuries. For all the blessings it’s bestowed on our species, the veneration of scientific inquiry has made Westerners skeptical of transcendence and its attendant allowance for the supernatural.

Rousseau’s state-of-nature premise gave a green light to thumbing our noses at convention. Marx’s class struggle formulation obscured the role of ingenuity in human advancement. Freud’s assertion that sexual impressions made upon infants dictate individual development diminished the role of personal responsibility while giving an outsized role to the sexual dimension.

Those forces have been converging with accelerated momentum since the middle of the last century. In recent decades, this has made a great number of claimants to the conservative mantle ever more frantic in their attempt to resist.

The Freemen News-Letter publishes all its content for free thanks to the generous donations of its supporters. Please consider joining those who value our efforts to elevate the political and cultural dialogue in America by offering a one-time, monthly, or annual donation.

What they’ve lost in their scramble to protect the stool legs or canons from this assault is the core of what they think they hold dear. Without that core, everything else they argue for in columns, podcasts, and legislative floor speeches is susceptible to attack. That core is an absolute conviction that there are immutable verities.

The above-mentioned shorthand is fraught with the danger of leaving out this essential conviction. “Social conservatism,” for instance, rather poorly covers the now-eroding assumptions about human sexuality that had served humankind since its emergence. “Free-market economics” only superficially encompasses the fact that agreements on the value of things to be exchanged, freely entered into, are rooted in a basic freedom of choice that makes human existence worth living. The terms “vigilant foreign policy” or “strong defense” only offer glimpses of the uniqueness of the conservative vision among the ways societies have been organized throughout history and the importance of its preservation.

In the last eight years, a certain kind of conservative has been motivated by desperation born of alarm at society’s transformation. That’s led to the near-worship of a figure who, when convenient for him, has talked, as well as he can articulate anything, the language of conservatism, but has only done so in the service of his own glorification.

Attempts to confer some kind of coherence to this desperation have given rise to talk about “populism” and “national conservatism.” Both terms presuppose a movable center to what they claim to hold dear. They’re predicated on the idea that conditions specific to our times warrant adjustments to the basics of an identifiable conservatism.

The common-good notion, and the outright industrial policy of which proponents sometimes unabashedly speak, would require conservatism to jettison the aspects of its foundation bequeathed by Adam Smith, Frederic Bastiat, Henry Hazlitt et al. Economic liberty is inseparable from any other kind, and it happens on the micro, not the macro, level.

The desperate “conservative” looks with disdain at Western support for Ukraine’s struggle to withstand naked aggression, citing the dollars spent on that undertaking vis-a-vis domestic concerns. This flies in the face of an understanding of the indispensable role the West has had in simultaneously holding barbarism at bay, as best as has been achievable, and spreading the tenets of its own robustness—representative democracy, the free market, and the dignity and worth of the individual—to more of the rest of the world.

It’s a decidedly conservative notion that sovereign nations’ borders should not be altered by force. History shows us that once that notion has been disregarded, precedents are set that are not restored without much chaos.

Politics, even in a heretofore successful representative democracy such as the United States, is, given our fallen nature, an ugly business. That politicians in elections, or bills in a legislature, must be dragged across the finish line in a manner that requires decent people to hold their noses, is an inevitability.

Does there not, though, come a point at which those with a working moral compass must opt to bow out? If there is no such point, the whole notion of immutable verities must go underground while darkness prevails.

The matter, then, of who gets to legitimately wear a particular ideological mantle is no triviality. It is of the most pressing importance for those who understand this to respond to the characterization of any American television network or even minimally viable Republican presidential candidate who claims to be conservative by saying, “No, they’re not.”

Barney Quick is an Adjunct Professor teaching Jazz and Rock & Roll History at Indiana University Columbus. He received his Bachelor’s degree in English and Literature from Wabash College and his Master’s degree in History from Butler University. @Penandguitar

Currently, all freelance contributors to the Freemen News-Letter have volunteered their writing abilities Pro Bono, but one of our major goals is to have enough cash on hand to pay those who offer their submissions freelance fees for their efforts. If you value the written word as we do, please consider offering a one-time, monthly, or weekly donation to the Freemen Foundation and help us with this goal.

Well put and well argued. Conservatism requires recognizing that there are timeless truths. Beyond that, we may have our disagreements, but that is one of the bedrock principles that could define right from left. I like George Will’s Conservative Sensibility for a synthesis of American conservatism, even as I have my disagreements with Will on questions of religion and God.