Every year, as the 4th of July approaches, I brace for the inevitable attacks against America’s Founding. Such attacks have become common, serving as a form of catharsis for those Americans, mostly of the progressive left, ashamed of their country. Our contemporary political culture has served only to heighten the level of vitriol directed towards the Founding. This ire arises chiefly from the indisputable fact the Founders were flawed, and many, though not all, owned slaves.

Some members of the intelligentsia even support the dismantling of all public works honoring the Founders. These statements validate and confirm the predictions of former President Trump and other spokespersons of the right. No longer simply outlandish fear-mongering, one can’t help thinking such statements from the left are made with the direct purpose of eliciting more conspiracy-laden responses from the right. Ironically (or tragically?), the far left and far right find themselves in a symbiotic relationship, each relying on the other to increase “likes,” “retweets,” and “followers.” Online conservative culture is driven by the phenomenon of “owning the libs;” met by its leftward cousin, “triggering the conservs.”

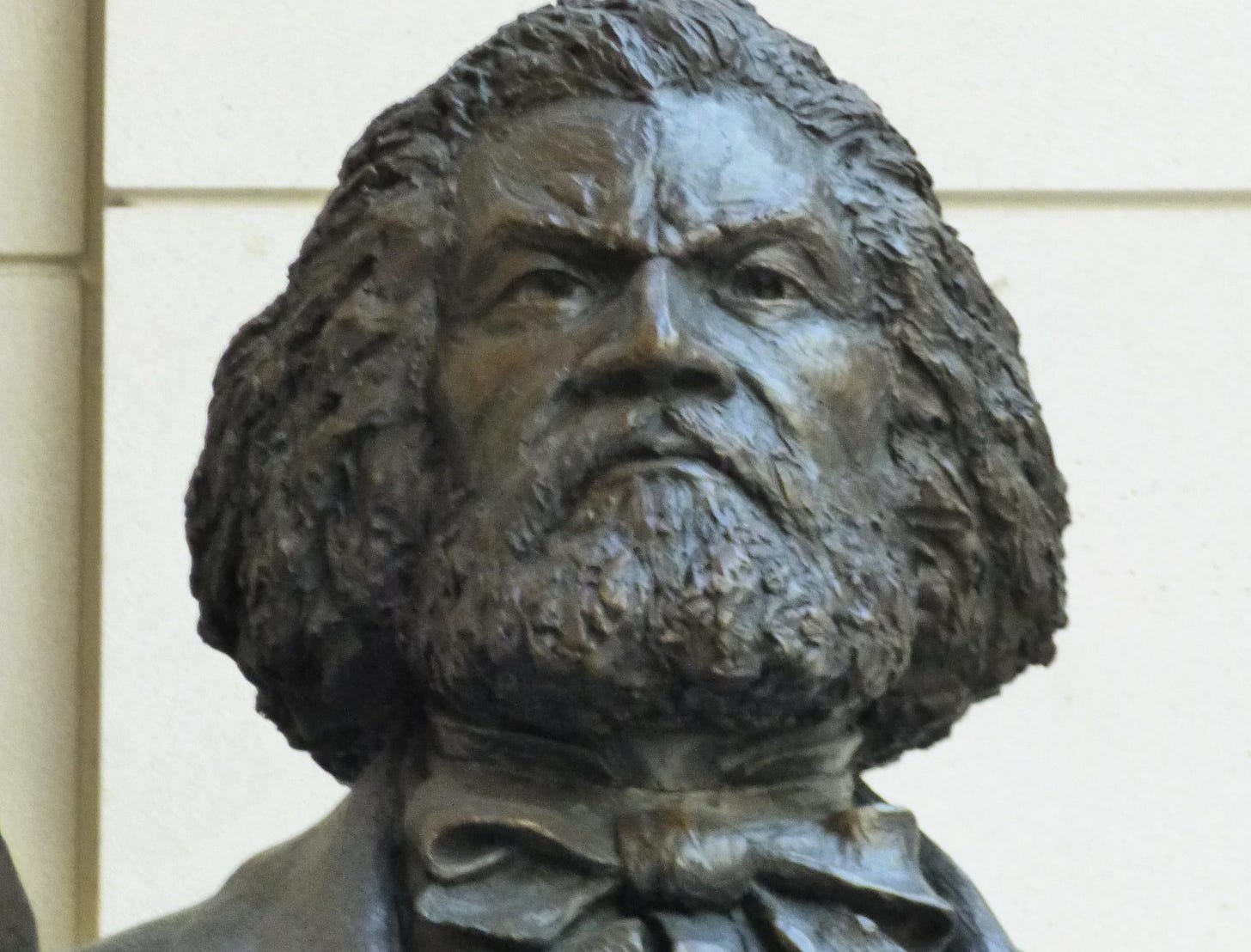

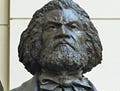

One tradition I have come to anticipate, accompanied with an eye roll and deep sigh, is the yearly ritual of plastering excerpts from Frederick Douglass’s speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” across social media. Delivered in 1852, Douglass’s speech rightfully deserves a place in the canon of great American political speeches. It was “a sacred effort,” as Douglass himself called Lincoln’s Second Inaugural thirteen years later.

With the power of his oratory and eloquence on full display, Douglass unleashed a scorching indictment of the hypocrisies and failures of a nation born proclaiming “all men are created equal.” A land “conceived in liberty,” to use Lincoln’s phrase, had allowed for the continued subjugation and bondage of millions of black men, women, and children. These sections of Douglass’ speech now serve as a creedal statement in the yearly liturgy of denouncing the Founding.

I find nothing objectionable in the speech itself nor do I take issue with people quoting it. My objections arise when keyboard warriors crudely use excerpts from a 10,000 plus word speech, often in the form of memes (not known as the best medium for learning history), to casually condemn American Independence. Indeed, if read in its entirety, those who invoke the speech to discredit the Founding may be shocked to learn a scandalous, almost cancel worthy fact. Frederick Douglass was a passionate defender of America’s Founding.

To understand the historical context of the speech, look no further than this interview from the National Constitution Center with two leading Douglass scholars, historian David Blight and political theorist Lucas Morel. Blight, whose Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Douglass may very well live up to the status of “definitive,” calls the speech “a symphony in three movements.” Most excerpts shared on social media come from the lengthy “second movement,” where Douglass laid out “the litany of all the horrors of slavery.”

One can easily see why those seeking to discredit the Founding are attracted to the “hailstorm,” as Blight calls the speech’s second act. The moral force and rhetoric employed by Douglass in this section was such that if safe spaces existed in 1852, the crowd would have needed them. Thankfully, they did not exist. The crowd heard the hard truth. America was failing to fulfill the lofty ideals of its Founding. Yet to truly appreciate the power of the “second movement,” one must start with the speech’s first section.

Douglass opened the speech by drawing his audience in, declaring, “It is the birthday of your National Independence, and of your political freedom. This, to you, is what the Passover was to the emancipated people of God. It carries your minds back to the day, and to the act of your great deliverance.” Note the use of “you” and “your.” Douglass established a certain distance from this celebration of freedom, even delivering the speech itself on July 5. But he also referred to his predominately white audience as “Fellow-citizens.” Douglass, then, was claiming a deep civic bond with his audience while simultaneously pointing to the gulf that existed between them.

In this first section, Douglass did not simply praise the Founding abstractly, but praised the Founding Fathers specifically:

“Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. They were great men too — great enough to give fame to a great age. It does not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great men. The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory.”

The second to last sentence above provides an important lesson for those modern Americans who seem capable of only denouncing the Founders. Douglass, though “compelled to view them” from the eyes of an ex-slave denied equal citizenship, still admitted he could not “contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration.” Embodying a maturity and nuance towards the past sorely lacking today, Douglass announced, “for the good they did, and the principles they contended for,” he would “unite” with his audience to “honor their memory.”

Concluding the first section, Douglass has the crowd where he wants them. Demonstrating a sincere appreciation for the Founding, he established a bond with his audience built on mutual admiration for the revolutionary generation. This bond amplifies, not diminishes, the coming blow. Hearing the truth about your failures from a friend stings far worse than hearing it from an enemy.

Douglass opens section two with a series of rhetorical questions:

“Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?”

The silence between Douglass’s fiery words, broken only by an occasional murmur or nervous laughter, one can imagine the smiles of Douglass’s audience fading. Replaced with looks of confusion and concern, they wonder where exactly he’s going with this. All the while, he marches relentlessly forward, drawing from the deepest wells of moral imagination, revealing the depths of America’s “national inconsistencies.”

Crescendoing towards the climax of the speech, Douglass bluntly states, “This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.” A few paragraphs later, Douglass deploys his most powerful denunciation in what had become the speech's most well-known passage:

“What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.”

Here, he lands a rhetorical body shot, knocking the breath out of any in his audience who would dare tout American liberty. “The existence of slavery in this country,” Douglass declared near the second section’s conclusion, “brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretence, and your Christianity as a lie.”

Douglass promised to “use the severest language I can command.” This he did. The severity of language should not obscure the depth and breadth of learning displayed in the speech. Douglass, channeling equal parts the Prophet Jeremiah and the radical deist Thomas Paine, drew from both the Biblical tradition and the Enlightenment’s natural rights tradition. The synthesis of intellectual history employed by Douglass, combined with the power of his oratory, leads Blight to call this speech “the rhetorical masterpiece of American abolition.”

One section of this “masterpiece” remains.

Transitioning from the second to the third section, Douglass noted there were those who claimed all the horrors and injustices of slavery he “denounced” were “guaranteed and sanctioned by the Constitution of the United States” as “framed by the illustrious Fathers of this Republic.” In contrast to the “honest men” Douglass proclaimed the Founders to be in the first section, those who enlisted the Constitution to defend slavery suggested the Founders “were the veriest imposters that ever practiced on mankind.” Douglass vehemently disagreed with those who charged such “baseness on the framers of the Constitution of the United States.”

Americans who use this speech to denounce the Founding or the Constitution as explicitly pro-slavery find themselves in stark disagreement with Douglass. Instead, they find themselves, ironically, in agreement with supporters of slavery who made the same argument: that the Constitution was designed to protect slavery.

This odd alliance between ideological opponents is not new. Elements of the abolitionist movement, chief among them William Lloyd Garrison, made similar arguments at the time. Garrison went so far as to burn a copy of the Constitution, denouncing it as “A Covenant with Death and an Agreement with Hell.” Since Douglass opposed both the Garrisonian and pro-slavery interpretation of the Founding, one assumes he would equally oppose the anti-Founding views of modern self-loathing Americans.

While the sheer power of the second section of the speech will always stand out, arguably, the most radical sentences come near the conclusion. “The Constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT,” Douglass boldly declared. He implored his audience to “Read its preamble, consider its purposes. Is slavery among them? Is it at the gateway? or is it in the temple? It is neither.” As the “charter of our liberties, which every citizen has a personal interest in understanding thoroughly,” Douglass was convinced the Constitution contained “principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery.”

Lucas Morel points out Douglass could use “incendiary” language “as well as any abolitionist of the day," but what makes this speech truly shocking is this was the “first speech where he announced that he had a change of heart and mind in particular about the constitution." Douglass refused to stay in his echo chamber. He read widely, thought critically, and, in the end, changed his mind. After his courageous fight against slavery and passionate defense of the Founding, Douglass’ truly liberal approach to learning may be his greatest lesson for us today.

“Notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation,” concluded Douglass, “I do not despair of this country… I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.” And where did this “hope” come from? He found it in “the Declaration of Independence, the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions.” Douglass ends the same way he began, with a passionate defense of the Founding. His powerful condemnation of slavery in the second section of the speech came not from a hatred of America, but a deep love for the promise held in the nation's Founding Charters.

In defending the Founders, the Declaration, and the Constitution, while harshly criticizing the nation for failing to live up to the principles it proclaimed, Douglass revealed himself to be that most unfashionable thing: a patriot.

Regarding the 4th of July, Douglass encouraged his audience, “Cling to this day — cling to it, and to its principles, with the grasp of a storm-tossed mariner to a spar at midnight.” Douglass did so himself, keeping faith in America while pushing it to embrace its “better angels.” On January 1, 1863, this faith was rewarded with Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. During a speech praising the proclamation, Douglass made an ingenious argument:

“Mr. Lincoln has not exactly discovered a new truth, but he has dared, in this dark hour of national peril, to apply an old truth, long ago acknowledged in theory by the nation—a truth which carried the American people safely through the war for independence, and one which will carry us, as I believe, safely through the present terrible and sanguinary conflict for national life, if we shall but faithfully live up to that great truth.”

The Constitution provided the framework that gave birth to our Union in the perilous years following independence. This same Constitution provided the mechanisms that preserved our Union during the crucible of our existence in the war from 1861-1865 and then redeemed our Union with the Reconstruction Amendments. Slavery was abolished, and the principle of equality stated in the Declaration was now enshrined in the Constitution itself via the 14th Amendment.

Eric Foner calls this moment our "second Founding," but it may be more accurate to say it was the culmination of forces that had been at work since the beginning of the nation and had been present during the drafting of the Constitution in 1787.

Douglass viewed Lincoln’s act of emancipation not as a break with the past nor a great constitutional innovation, but the correct implementation, after far too long a delay, of existing constitutional and natural principles rooted in the moral imagination expressed in the Declaration. It may have been a "crooked path to abolition," but the area was cleared when 39 imperfect men signed an imperfect document on September 17, 1787.

Imperfect men? An imperfect document? Absolutely. But at least a path could be made. It would take a statesman like Lincoln and a prophet like Douglass to make sure the path of abolition was followed.

Today, partisans on both sides of the political spectrum insist the 4th of July and Juneteenth are separate, and tragic few even take heed of Constitution Day. They insist Americans must choose what we celebrate, independence and our Founding, or emancipation and abolition. Douglass understood the fallacy of such arguments. He knew the great truth.

American independence and abolition, the Declaration of Independence and the Emancipation Proclamation, the Bill of Rights and the Civil Rights Acts, are all intrinsically linked. They are inseparable and indivisible. May all Americans come to cherish this great truth.

Kenly Stewart is a freelance writer researching and writing on a range of topics addressing politics, religion, philosophy, and history. He completed undergraduate studies in history and religion at Campbell University, and received his Master of Divinity from Wake Forest University. A proud public school teacher, he currently teaches high school social studies in North Carolina. @StewartKenly

That speech is absolute proof of Douglass' skills as both a writer and an orator. He knew his personal voice, he knew his audience well, and he used both to his advantage.

Douglass was borrowing directly from Isaiah: "I can't stand your New Moons, Sabbaths, and other feast days; I can't stand the evil you do in your holy meetings. I hate your New Moon feasts and your other yearly feasts. They have become a heavy weight on me, and I am tired of carrying it."