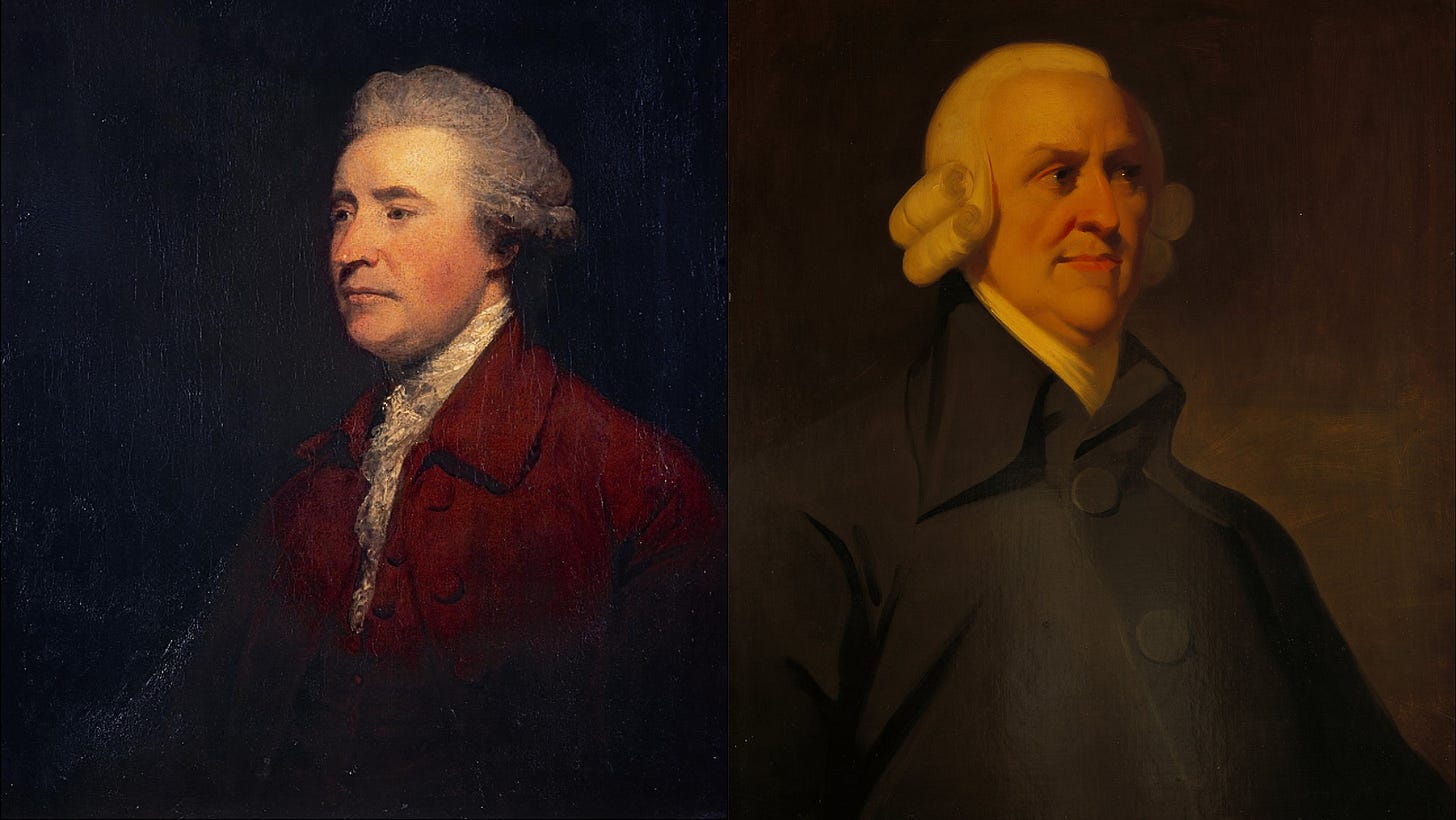

Edmund Burke, Adam Smith, and Fusionism before “Fusionism”

The partnership of free markets and traditionalism has a much older history in the Anglo-American tradition, and thicker philosophical compatibility, than fusionism's detractors are willing to admit.

Fusionism (the partnership between cultural traditionalists and free-market libertarians) is often described as being developed in the 1950s by William F. Buckley and Frank Meyer, who used the shared fight against communism to bring the two camps together in a supposedly ad hoc fashion. However, the partnership of free markets and traditionalism has a much older history in the Anglo-American tradition, and has thicker philosophical compatibility than is often recognized, as evidenced by the friendship and political alliance between Edmund Burke and Adam Smith.

Edmund Burke, often described as “the father of conservatism,” served in the British Parliament as a member of the Whig Party from 1765 to 1794, championing traditionalism and incremental reform to the monarchy, imperial colonial policies, and the economy more broadly. Burke advocated for the maintenance of a living tradition flexible and pragmatic enough to adapt to unfolding circumstances. He famously stated, “A state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation.”

Burke opposed the left-wing ideologues of his age. He criticized the French Revolutionaries for their hubris in thinking they could re-engineer human nature and French society from scratch. Burke warned against the ideologue who “consider[s] his country as nothing but carte blanche, upon which he may scribble whatever he pleases.” Burke was not categorically against revolution. He approved of the British Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the American Revolution of 1776, which he understood as efforts to recover and build upon ancient rights and traditions. In contrast to these, the French Revolution was, in Burke’s view, a reckless utopian scheme seeking to sever the French nation from its historical and religious roots.

Burke thought the role of the policymaker was not to remake ”society otherwise constituted than he finds it,” but to “make the most of the existing materials of his country.” In his view, a statesman needed a “disposition to preserve and an ability to improve.” Burke had a deep respect for the wisdom of the common man and the role of decentralized knowledge in society. Traditions were valuable because they were the product of many minds through a process of trial and error over long periods of time. He said, “I have never yet seen any plan which has not been mended by the observation of those who were much inferior in understanding to the person who took the lead in the business.” Burke’s aversion to top-down schemes by elites to socially engineer society and his regard for decentralized knowledge held by the common man overlapped with much of the thought of Adam Smith.

Smith is primarily known for helping launch modern economics and for his attack on trade restrictionism. Smith’s advocacy for free markets and free trade was predicated on, not merely abstract theories, but observations of concrete failures of the British mercantile system. He perceived that the flowering of industrialism in northern England and Scotland took place despite, not because of, central planning coming out of London.

Smith believed that the rigors and demands of free markets generally cultivated virtues such as discipline, fair dealing, sobriety, punctuality, and hard work among the middle class. But he was not naive and recognized extreme wealth and unbridled desire for distinction were corrosive for those at the top of the economic pyramid. For these reasons, Smith saw government as justified in implementing some reasonable limits on markets and even advocated for caps on interest rates.

He saw the division of labor as economically efficient, almost miraculously so, but recognized that it could have a potentially deadening effect on some in the workforce. Consequently, he advocated for public education. Unlike later, more utilitarian capitalists who thought that the ultimate purpose of public education was to shape the masses to be useful cogs in the economic system, Smith thought that education should be designed to protect the humanity of the worker from being totally subsumed by occupational drudgery. Overall, the role of government was mostly reactive, responding to concrete problems remedially or in a modestly preventative way, to the extent clear evidence of destructive patterns arose. The role of government was emphatically not to reshape human nature nor to establish some new Eden based on theoretical principles.

Smith, like Burke, was averse to rigid ideologies. He warned:

“The man of system…is apt to be very wise in his own conceit; and is often so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he cannot suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it. He goes on to establish it completely and in all its parts, without any regard either to the great interests, or to the strong prejudices which may oppose it. He seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board. He does not consider that the pieces upon the chess-board have no other principle of motion besides that which the hand impresses upon them; but that, in the great chess-board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might choose to impress upon it.”

-Adam Smith, Theory of Moral Sentiments

Burke and Smith shared what David Brooks has called “epistemological humility,” an appreciation of emergent orders based on decentralized knowledge, and a vigilance against quixotic efforts to reconfigure society based on abstract principles. Modern historian Walter Russell Mead describes how this typically Anglo fascination with emergent orders (what Mead calls the “Golden Meme”) also lies at the root of the English development of the common law over centuries, Francis Bacon’s scientific empiricism, John Milton’s defense of freedom of speech, and Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Ironically, Burke was arguably a more adamant free-marketer than Smith in some respects. In his 1795 Thoughts and Details on Scarcity, Burke strongly rejected the idea of providing wage subsidies to poor laborers in times of scarcity. In contrast, Smith was mostly silent on the question of government-implemented poor relief but was more vocal than Burke about the corrosive effect of poverty in society. Smith said, “It is but equity…that they who feed, clothe, and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of so much of their own labor as to be themselves tolerably well fed, clothed, and lodged.”

Both Burke and Smith were influenced by the Stoic idea of oikeiôsis, articulated by Hierocles, in which human affections and attention are naturally ordered in a way that begins with those closest to us (our family and local communities), and then by steps out toward the broader world. According to Burke, “To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections. It is the first link in the series by which we proceed towards a love to our country, and to mankind.” Similarly, Smith said, “That wisdom which contrived the system of human affections, as well as that of every other part of nature, seems to have judged that the interest of the great society of mankind would be best promoted by directing the principal attention of each individual to that particular portion of it, which was most within the sphere both of his abilities and of his understanding.”

Smith’s oikeiôsis seems the more constrained of the two. Burke’s “little platoons” served the ultimate purpose of training persons for service to broader mankind. In contrast, Smith is more explicit about the importance of not going too far beyond our designated spheres, our country, local community, and family. According to Smith, “the universal happiness of all rational and sensible beings is the business of God and not of man.”

Both Burke and Smith were voices for restraint in foreign policy and challenged Britain’s colonial policies. Burke’s criticisms were more concrete and granular. He famously led the prosecution of the impeachment of Warren Hastings for his mismanagement and corruption during his governorship in India. He also sympathized with the American Revolutionaries' specific complaints about Parliament’s colonial policies. Smith’s criticisms of British colonial policies were much broader, arguing that the British colonial global enterprises were often vanity projects and would deplete more resources than they generated for the benefit of Britain.

Burke and Smith’s insights are well-suited for modern American conservatism’s challenges today. Currently, there is widespread public frustration with the disastrous failures of our overly ambitious elites. The public is confronted with visible, tangible manifestations of these failures: crime-ridden cities, increasing murder rates, an overwhelmed border, academics and students at elite universities supporting Hamas, cities overwhelmed by migrants, gender ideology indoctrination in public schools, and corruption among racialist ideologues such as Ibram X. Kendi and the BLM organization. It’s strikingly apparent that modern elite “men of system” have run amok and need to be reined in, that policymakers have become oblivious to facts on the ground.

Burke and Smith were by no means populists in the modern sense. However, they did have a profound respect for the common man, a vigilance against monopolies, and a deep concern about the machinations of unchecked elites. Smith famously warned, “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the publick, or in some contrivance to raise prices.” This rings as true as it ever did.

There are acute areas of tension currently between traditionalists and libertarians: immigration policy, abortion, same-sex marriage, and trade policy, to name just a few. Moreover, fusionists have taken a beating since the rise of Trump. Much of this is deserved because of fusionists’ failures in the realm of foreign policy in which they have failed to apply the insights of moderation, reverence for realities on the ground, and skepticism about efforts to redesign societies.

As fusionists muddle forward through the contemporary challenges, three important lessons from the thought of Burke and Smith stand out. First, traditionalists and conservative market-libertarians must cooperate and compromise. Again, Burke and Smith can serve as models for this, as described by Samuel Gregg in National Review from May of 2023. For example, Smith had long advocated the elimination of export subsidies. Yet Burke, in 1772, crafted a bill that continued the very subsidies Smith objected to. Burke lamented that it simply wasn’t politically feasible to completely do away with them. Years later, Smith graciously wrote of the bill that, although imperfect, it was “the best which the interests, prejudices, and temper of the times would admit of.”

Second, a guiding principle for such compromises should be a preference for proven, slowly emergent arrangements over untested schemes by elites that would consolidate power in their hands. Burke and Smith were vigilant against excessive concentrations of economic power, whether in the hands of government, monopolies, or cartels. By analogy, in the cultural realm, we cannot afford to be “men of system,” allowing ideology to handcuff us and prevent us from responding to predatory, top-down efforts (public or private) to manipulate and dehumanize the citizenry. We should not accept the idea that “liberty” means telling the electorate to hold still while their communities and traditions are trampled by social media companies, activist corporations, and a hyper-ideological educational establishment.

Third, fusionists must clearly communicate and be earnestly guided by Burke and Smith’s respect for the wisdom and virtue of the common citizen. William F. Buckley famously said that he would rather be governed by the first thousand names out of the Boston phonebook than the Harvard faculty. Ronald Reagan similarly grounded his embrace of markets and cultural traditionalism on reverence for regular people. In the past two decades, the Republican party has strayed from this in many respects.

An unfortunate example of this was Mitt Romney’s comments in 2016 about the forty-seven percent of the country who didn’t pay net federal income taxes. Romney seemed to imply (or at best allowed himself to be portrayed as implying) that half the country was not only mere takers, but narrowly self-interested to the point of being unable to put the good of the country over their desire for free stuff. The bitter irony was that the working class and middle class had long been derided by Democrats for failing to vote in their own economic interest. Worse, these supposed takers were often the parents and family of troops who had dutifully sacrificed for the good of the country in wars, the purpose of which was increasingly becoming unclear.

The good news is that traditionalists and free-market libertarians still—after more than two hundred years—have abundant reason to work together. The bad news is that this common ground is based on the reality that far too many of our elites are still delusional, far less competent than they think, and refuse to acknowledge the damage they’re causing. Fusionists have every reason to win going forward if we can only act with a fraction of the patience, grace, and good sense of those who came before us.

Nathan Brown is an immigration attorney in Fresno, CA. He received a BA in Economics and History from Brigham Young University and his Jurist Doctorate from Emory University School of Law. @nathankblbrown

Well-done!... A writing which could be of great use IF some of our leaders on both sides would take the time to read it. This caused me was to remember a college professor's class on "A Tale of Two Revolutions". Over one week, he compared the results of the French Revolution, in which virtually EVERYTHING was thrown out, with the aim to completely re-build ex nihilo...and the American Revolution, in which a foundation of basic values and policies was retained, to be built upon with time and additional insight. Our Founding Fathers were right and our "Great Experiment" thrived.

This was excellent 👏🏻👏🏻