Founding Vision: Forged in the Fire of Experience

The founding project was a perusal and debate on the first principles of government as gleaned from the light of human history, but it was tempered and forged by the lamp of experience.

Introduction and Thesis

Patrick Henry, though fitfully labeled a radical whig, nevertheless declared, “I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided, and that is the lamp of experience.” James Madison, though at times a political opponent of Henry’s, echoed the same sentiment in Federalist No. 20 where he says, “Experience is the oracle of truth; and where its responses are unequivocal, they ought to be conclusive and sacred.” In America’s founding era, we can observe the flowering and even the collision of various schools of thought and the traditions and understandings of constitutionalism, political theory, and governing philosophy. But the guiding star of this auspicious age was experience.

The realities of human nature and the facts of government in its exercise forged the perspectives of the founding era. They guided the thoughts, actions, and debates of the time toward the successful genesis of a new experiment in the organization and governance of human society. If there can be said to be a founding vision, it is in observing the collective thinking of the time and observing how the founding dialectic combined with the joint experiences and observations of its participants to lead toward the creation of a new form of government with a cornerstone of certain values, principles, and beliefs that, through a complementary tension, combined into a framework that grew into the most successful endeavor of free government in human history.

The purpose of this essay is to lay out the successive layers of the forging fire that refined the various actors and traditions of the founding era into a working whole and to demonstrate how the American republic came to exist as a functioning and thriving liberal republic through the rational consideration and application of the first principles of government through the prism of human experience.

Colonial America: English Constitutionalism and Whiggish Discontent

The American Revolution did not occur in a vacuum. Nor did it begin as a revolution in the general meaning of the word. Rather than a revolt against an established order or an insurrection against a general form of government, it was a rebellion against the policies of empire as exercised by the British Crown and endorsed by Parliament that the colonists felt was robbing them of their rights as Englishmen. It was, in many ways, a uniquely conservative revolution that sought to restore both the rights and form of government expected by adherents to the values of English constitutionalism, as well as the norms of a societal organization that sprang up as a result of the policies of salutary neglect.

When English colonists left their home country and migrated to America, they did so with the expectation that they remained subjects to the English Crown and retained the full rights of Englishmen. They organized society upon the principles of the Glorious Revolution, valued representative government, and established laws protecting the fundamental rights of life, liberty, and property. The philosophical roots of the American colonies, in so many ways, were established and grown according to Whiggish notions of rights and history, crafted on Whiggish ideas of government and liberty, and were watered and grew deep during an era of Whiggish domination in the Royal Court and the halls of Parliament in Great Britain.

The changes that precipitated what initially began as an English constitutional crisis in the governance of free colonies did not involve the colonists but involved the rise of a new Monarch and the return of Tories to power in the seats of British government. Before King George III came to the throne in 1760, the Tories had been essentially excluded from government altogether by King George I and King George II, a period known as the Whig Supremacy (during which time the policy of Salutary Neglect was in full force concerning the American colonies). Under King George III, however, Tories were not only allowed back into governance, he often favored them over Whigs given their propensity to support, and his belief in, more asserted monarchical absolutism.

King George III’s ascension to the throne, then, easily marks the beginnings of the trouble that would eventually culminate in Britain’s loss of their American colonies. It didn’t take long for the King and Parliament, thanks to the increased influence of the Tories, to essentially end the policy of Salutary Neglect and reinforce both the King and Parliament’s declared sovereignty and control over the American colonists.

First, beginning in 1763, the British government began enforcing the strict provisions of the Navigation Acts, which it had previously not enforced to any meaningful degree when it came to the American colonies under the policy of Salutary Neglect. This enforcement became supplemented by various taxation policies and authoritative acts by Parliament, including the following:

-Sugar Act of 1764: A tax levied on molasses in the American colonies to recoup the costs of defending the colonies during the French and Indian War. This tax was heavily resented by the colonists, who were in a state of economic depression at the time and had given generously of their substance to feed and equip British soldiers during the French and Indian War.

-Currency Act of 1764: A restriction of the issue of paper money by the colonies and in the creation of banks. The American colonies had limited capacities of gold and silver, and relied on paper money as a means of establishing consistent value of goods.

-Quartering Act of 1765: The granting to British military authorities in the American colonies the power to quarter soldiers among the population, taking public and private buildings as necessary for the establishment of barracks. The American colonists felt they had been put under occupation as there had been no British standing army in the colonies before the French and Indian War.

-Stamp Act of 1765: A direct tax on the American colonies requiring all printed materials to be made on paper from London and stamped appropriately. The American colonists resented such an exercise of power by Parliament in the absence of any meaningful representation in Parliament. The response to this act of Parliament made the clarion call “no taxation without representation” a popular sentiment in British America. Opposition to the Stamp Act culminated in the Stamp Act Congress, the first organized meeting of representatives from all British colonies in protest of Parliament's attempts to assert sovereignty over them. The Stamp Act Congress produced the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, among the first of the founding documents.

-The Declaratory Act: In many ways a mea culpa with an astrix from Parliament, the Declaratory Act passed simultaneously with the repeal of the Stamp Act and the amending of the Sugar Act. While the repeal and amendment of these acts was a major victory for the American Colonists, the Declaratory Act nevertheless rebuked their ideal of “no taxation without representation” by affirming the principle of Parliamentary sovereignty and declaring they had “full power and authority” to “bind the colonies and people of America...in all cases whatsoever." American colonists again felt treated as second-class citizens rather than full subjects with the same rights as all Englishmen.

-The Townshend Acts: A series of acts passed in 1767 and 1768 designed as both another attempt to force the American colonists to provide revenue for the British government and to bring rebellious attitudes to heel. Among other things, new taxes on most imports were introduced, consequences were levied upon New York for violating the Quartering Act, and the jurisdiction of colonial courts over matters of smuggling and customs was stripped away and given to royal admiralty courts. Response to the Townshend Acts was initially more muted than the response to the Stamp Act, but when opposition to the acts began bubbling up from colonial legislatures, British authorities responded by first restricting then dissolving colonial legislatures altogether, such as happened in Massachusetts. This only outraged colonists even more, and Boston became a hotbed for anti-British agitation. In 1768, British troops were moved into Boston, and the town came under occupation. The occupation was highly unpopular and culminated in the Boston Massacre in 1770. The Townshend Acts were symbolically repealed in 1770, though many of its core revisions remained in effect and Boston remained occupied by British regulars.

-Tea Act of 1773: Taxes on tea were one of the Townshend Acts that remained in force, but various successful smuggling operations circumvented such taxes. The act essentially granted a colonial monopoly to the British East India Company, which could import tea to the colonies duty-free as long as the Townshend taxes were paid. Colonists saw this as Parliament attempting to trick them into accepting British taxes on goods by making British East India Company tea much cheaper than the predominantly consumed, and smuggled, Dutch tea (the colonists would not pay taxes directly but would purchase tea upon which taxes had already been paid). The attempt to bring in the East India Company’s tea resulted in the Boston Tea Party and further inflamed tensions.

-The Intolerable (Coercive) Acts of 1774: A series of acts designed to punish Boston for the Boston Tea Party. They involved the closing of Boston Harbor, the appointment of Thomas Gage as military governor of Massachusetts, the stripping of Massachusetts’ colonial charter, and the quartering of troops in the homes of the colonists. Outrage toward the Intolerable Acts led to the First Continental Congress, which established the Continental Association and drafted the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress. These provisions together called for a general boycott of all British goods by American colonists, listed and enumerated the grievances of the colonies, and involved sending a petition to the King requesting the repeal of the Intolerable Acts.

All these acts taken together provide us a dizzying array of Parliamentary interference into a sphere that had previously been left generally to its own devices for generations. A people accustomed to self-governance and self-sustainment, with no history of even cursory taxation powers or authority asserted by Parliament and having no experience with standing armies or military governance, suddenly found themselves thrust into a brave new world.

The colonists who found themselves suddenly in the midst of military struggle with their mother country after the situation in Boston culminated in the Battles of Lexington and Concord were far from radicals seeking to tear down an undesirable status quo. Instead, they were men and women who found themselves facing the slow erosion of their traditional way of life, the corruption of their traditional processes and understandings of government, and the occupation by military forces who were supposed to be in the colonies for their protection and not their subjection.

The Declaration: A Mission Statement

The Declaration of Independence is powerful because, in several aspects, it went beyond the narrow scope of its purpose of simply declaring independence, taking additional steps toward the embrace and application of liberal principles.

In English constitutionalism, there had been a profound disconnect between its Lockean and Hobbesian parts. English and British political culture valued the protection of life, liberty, and property as part of the social contract and had aspects of popular sovereignty, especially as it championed the results of the Glorious Revolution and the philosophy of its defenders and philosophical progenitors, such as John Locke, James Harrington, and John Milton.

However, the English political system remained autocratic in the form of its monarchy, and Parliament jealously guarded its position as a sovereign body within the Empire. For all its Lockean frills, the British government remained a Hobbesian leviathan held at bay more by the expectation of political culture than meaningful checks and balances built into the governing structure. As touched on in the previous section, the colonial experience demonstrated how easily the English unwritten constitution could be violated when the Crown and Parliament found sufficient reason to do so.

In writing the Declaration, Thomas Jefferson laid the seeds for a political culture that would largely reject the Hobbesian view of security over freedom and embrace the Lockean belief in liberty for all. He also established what, in essence, became the mission statement of the founding project:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

In declaring its separation from Great Britain, the United States established its existence predicated upon a substantial departure from the autocratic aspects of British government and a much broader embrace of the liberal aspects of English constitutionalism.

The Revolution: Birth of a Nation

While the Declaration of Independence claimed to establish a new sovereign nation, the reality was that the former British colonies remained a squabbling collection of separate states with unique identities, interests, and citizens who did not view themselves as part of a national American whole. This sense of national identity would instead be forged in battle against British designs to put down the rebellion.

The patriot cause gained a common hero in George Washington. Soldiers who volunteered to fight under the banners first of colonies and then of independent states found themselves fighting under the banner of a single nation, and began thinking of themselves as Americans. Ordinary people who were either ambivalent to the patriot cause or were actively hostile to it found themselves nevertheless subject to the punitive treatment of British occupation, and were pushed towards the support of the common cause of American independence.

The rise of American nationism required the forging fire of struggle against British attempts to re-subjugate its wayward colonies. While the Declaration of Independence established the rebelling colonies as “the united States of America,” the vast majority of this new nation’s inhabitants did not think of themselves as Americans nor held identities that were connected to the national whole, instead grounding their loyalties to communities, churches, and, at most, their newly established independent state.

There were a few, such as George Washington, who immediately saw the struggle against Great Britain as a unifying call to form together under a single banner. But, as the Second Continental Congress’ struggle to agree on the idea of independence let alone on the wording of the document that would decalre dependence demonstrated, the predominant loyalty of even the leading thinkers of the day remained grounded in locality.

One example of this early disunity is the 1776 Christmas riot at Fort Ticonderoga. Simmering tensions between the Pennsylvania and Massachussetts soldiers that manned the fort culminated in a Christmas Night altercation that involved a Pennsylvania officer leading dozens of Pennsylvania soldiers in a raid against the Massachussetts soldiers, shouting the battle cry “Damn Yankees!” They even opened fire with their muskets on the Massachussetts tents and huts.

While the above riot is an extreme demonstration of disunity between the states (one that was quickly put down and covered up so as not to betray any weakness to possible allies, such as the French, after finally securing symbolic victories in Trentona and Princeton), fights and tense standoffs between units from different states over simple things such as camp locations and bathing in rivers happened quite regularly.

Overtime, however, the Continental Army became America’s earliest symbol of national unity, with its leader, George Washington, becoming the first true national symbol, a man who was able to transcend local and state loyalties in the affection of his countrymen.

Valley Forge, specifically, is often cited as an incredibly unifying period of time for the Continental Army. The combination of the trials and tribulations of that horrendous winter, the respect and distinction Washington earned from his men by sharing in their travails and keeping faith with them, and the training and discipline afforded by Baron von Steuben forged the Continental Army, not only into a far more proficient fighting unit, but into an army with a higher sense of identity beyond local and state loyalties.

The Constitutional Army became a national institution, it’s victories gave the citizens of the new nation a sense of national pride, and veterans returned home sharing and spreading a new sense of national identity.

The Confederation: A Steep Learning Curve

Through their experience in self-governance during the Revolutionary War and afterward, Americans learned that re-establishing the free society they felt had been encroached upon by British authority was far more difficult than they had assumed.

The British hierarchy, even under salutary neglect, had provided a throughline for both economic organization and general cultural allegiance that allowed thirteen separate colonies to thrive. Without at least the image of the crown to keep colonies bound to general cooperation and without any overarching authority to establish the boundaries of state government action, the newly independent states became hotbeds of legislative overreach. Hostility and disagreement between the states seemed to be marching towards inevitable conflict.

James Madison, for example, “saw the need to create a stronger national government to thwart the rise of unrestrained democracy, which, [he] believed, threatened the very republican principles for which Americans had fought and died.”

Beyond political theory, serious trouble existed in political reality, such as the business of Shay’s Rebellion, a revolt largely engaged in by Revolutionary War veterans in response to actions of the Massachussetts legislature that painfully reminded them of the actions of Parliament which they had rebelled against only a decade before. These measures, which John Adams described as "heavier than the People could bear," began with excessive taxation schemes to pay off debts accrued during the war and culminated in limitations on freedom of speech and the suspension of Habeus Corpus.

Not only does Shay’s Rebellion demonstrate the excessive actions of state legislatures unchecked by an effective national charter of limited government, it also demonstrated how ineffective states were in maintaining the rule of law and putting down rebellion. Local militias were ineffective against the rebellion, as many of its members were also part of the rebellion. And keeping temporary state militias in the field proved extremely difficult.

Slowly, American political thinkers and leaders began to realize that the dream of re-establishing society as it had operated under salutary neglect wasn’t possible. The circumstances of life in former British colonies of America had changed, as has the political realities that impacted everything from commerce and law to culture and popular sentiment. Something new, indeed something truly revolutionary, would have to be created.

The Convention: The Great Debate

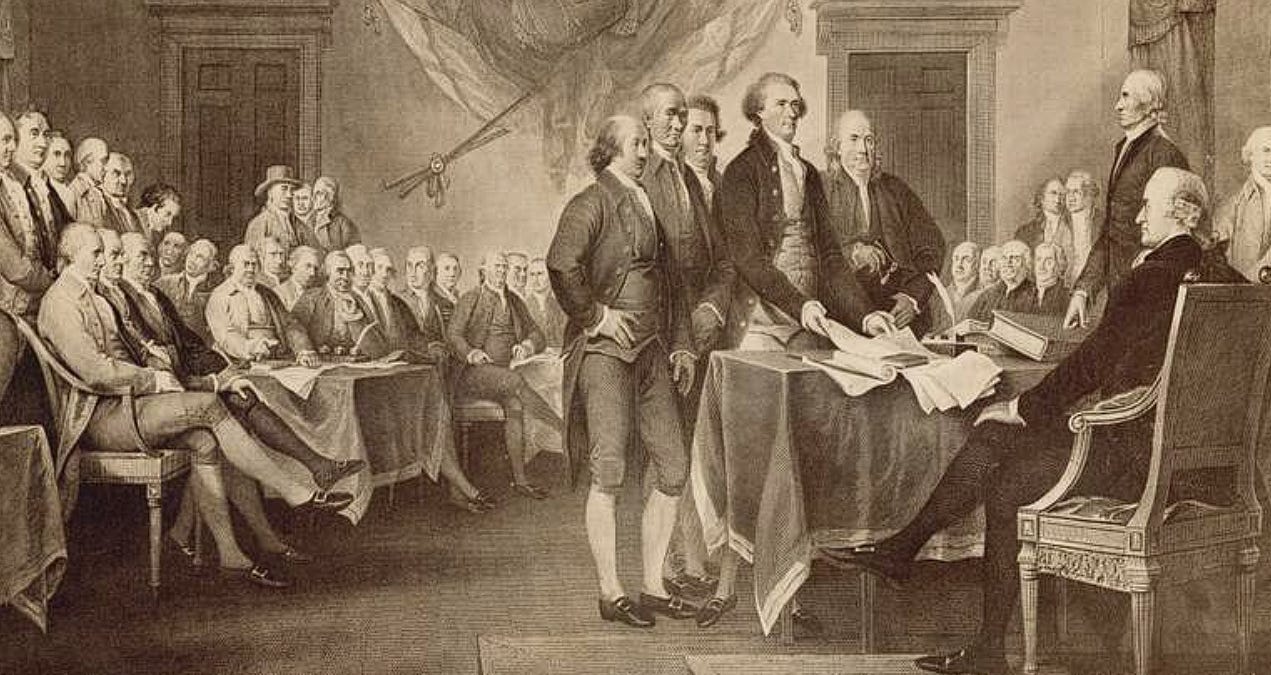

To address the defects of the Articles of Confederation, a Federal Convention was called in Philadelphia. Thomas Jefferson called the group of delegates that we now refer to as the framers “an assembly of demigods.” The attendants had general agreement on many issues but were adherents of several different philosophical traditions and had sometimes dramatically different ideas of how the government should be constituted.

Three branches of republicanism can be identified among the framers: classical republicanism, liberal republicanism, and democratic republicanism. Much of the debate that would ensue in the convention was between these three outlooks and how to organize the government according to their precepts or in compromise between them.

The different outlooks of republicanism all held general agreement on certain basic principles. They agreed the best form of government was representative and that the government should be limited in its scope by a written constitution. They agreed that the Articles of Confederation had been too weak and that a stronger general government was necessary to hold the union together. And, they agreed on the idea of mixed government and separation of powers and that legislatures unbound from established limitations could be just as apt to tyranny as a monarch.

Indeed, it could be said that the outlooks generally agreed on all the basic ingredients we would recognize as underlying the American Republic. But it was in their emphases where their differences could be stark, and these emphases would lead to disagreements over how to order government to accomplish the agreed upon goals of a constitution.

Simply put, liberal republicanism’s emphasis was on liberty, classical republicanism’s emphasis was on virtue, and democratic republicanism’s emphasis was on popular sovereignty. The fundamental conflicts in these visions occur at the intersection of their most important principles. Should liberty be emphasized to the detriment of public virtue? Should virtue be cultivated at the expense of popular sovereignty? Should popular will be allowed to subvert liberty?

While the Federal Convention was not necessarily a theoretical summit where these different philosophies were debated outright, these themes underlined many of the arguments over the provisions of the US Constitution. The Congregationalists, for example, with their Puritan roots, weren’t afraid of stronger government and the overt use of governing power to promote virtue in society, and were among the advocates for a stronger central government. But Southern agrarians were enamored with the rugged individualism of independent land ownership, and valued giving common people a greater say in the halls of government. And then there were the Quaker influences that had allowed places like Philadelphia to flower as bastions of individual liberty with desires for protections for minorities against the tyranny of majorities.

It would be too much to assert that the framers found philosophical harmony at the Federal Convention. In fact, no one saw the US Constitution as a document wholly reflecting their views in a way that fully enamored themselves to it. Several of the key delegates who served as chief architects of many of the Constitution’s provisions, such as George Mason, Elbridge Gerry, and Edmund Randolph, refused to sign the completed document. Many others were concerned the entire enterprise was a dissatisfying compromise that earned their begrudging support so that it could accomplish the end of the Confederation, with hopes of fixing and altering the document later on through the provided amendment process.

But there were some inklings at the convention of what it was they had wrought, and that perhaps they had, in fact, succeeded in fusing the various republican traditions into a working project in free government. We can glean several quotes from Benjamin Franklin’s final speech at the convention to typify both these general feelings as well as the inklings some had begun to sense.

In his speech, Franklin acknowledged his apprehensions, confessing that he did “not entirely approve of this Constitution at present” and commenting on “all its Faults.” He, however, also considered that he was “not sure [he] shall never approve it” and consented to the Constitution “because [he] expects no better, and because [he was] not sure that it is not the best.” He remained of the opinion that the Consitution had “errors” but was nevertheless astonished “to find this System approaching so near to Perfection as it does.” Ultimately, he decided that because he thought “a General Government” was “necessary for us,” he was willing to “sacrifice to the Public Good” his concerns with the faults and errors of the Constitution as drafted by the convention.

Ratification: Conversion by way of Debate

Often, discussion of the framers’ thoughts on the constitutional provisions they crafted stays exclusively within the Federal Convention itself. But the story of ratification is an important part of the story. That which we term American constitutionalism largely derives from arguments of those on both sides of the ratification effort.

Resources such as the Federalist Papers and the Anti-Federalist Papers are treasure troves for those seeking to establish how both the framers, in particular, and the founders, in general, evolved on their views of what had been created at the Federal Convention.

The Federalist Papers specifically gives us a lot of evidence in support of the conclusion that many of the framers who went into the convention with different expectations and came out of the convention supportive but disappointed with the Constitution eventually gained a stronger conversion to its contents as they engaged in the debate for its ratification.

James Madison, for example, had brought a very different plan for government (though foreshadowing many eventual provisions of the US Constitution) to the convention and argued aggressively against many of the measures that were eventually adopted.

At the convention, Madison arguably leaned far heavier into the classical and democratic strains of republicanism. And yet, in the Federalist Papers, Madison lays out one of the most effectual and thorough defenses of a liberal republic perhaps ever penned. And, it was Madison who went on to assemble and propose the Bill of Rights, the amendments that tipped the scales into firmly establishing the American Republic as a product of classical liberalism. (Madison, unlike any other founding father, existed philosophically at the fusion of sovereignty, liberty, and virtue.)

The Bill of Rights: Founding a Political Culture

As was just mentioned in the previous section, the Bill of Rights is perhaps the most classically liberal aspect of the US Constitution. While the rest of the document mostly deals with the processes of government, the first ten amendments go considerably further in limiting the scope of government and establishing its purpose as a defender and protector of individual freedom.

But if this were all the Bill of Rights accomplished, the various arguments against its creation would carry considerable weight. The history of the American Republic has demonstrated that when an enumeration of rights occurs, those rights left unenumerated tend not to be protected.

However, the Bill of Rights did accomplish much more than a legal enumeration. The Bill of Rights provided the foundation of a political culture that could match the creation of the mechanisms of a liberal republic. As James Madison stated when he grew more convinced of the value of a declaration of rights, “The political truths declared in that solemn manner acquire by degrees the character of fundamental maxims of free Government, and as they become incorporated with the national sentiment, counteract the impulses of interest and passion.”

The Bill of Rights helped to solidify what came to be American constitutionalism, and established a political culture, an unwritten constitution, that allowed the written constitution to function as intended.

Conclusion

In many ways, the Bill of Rights completed the circle of the founding experience by linking the result with the declared values of its genesis in the Declaration of Independence. While there are indeed many different traditions of thought and philosophy involved in the founding project, and it would be generous to say that all the founders and framers were in full agreement over what the finished product was and its value, we can nevertheless observe that while the elements of classical and democratic republicanism are important aspects of the American Republic, it is nevertheless liberal republicanism that fills the majority of parts in America’s representative government.

But all these traditions exist within the framework of the Republic. The journey of American history has been an ongoing conversation and debate on the various traditions and beliefs that existed in the founding era and were represented at the Federal Convention. The presence of each creates the tension necessary for affording a balance of concerns, without which the whole project would unravel.

The fusion of the concerns of liberty, virtue, and sovereignty into a workable cohesion has been demonstrated to not only be eminently workable, the history of the project has also demonstrated that far from an artificial grafting, these social goods can only truly exist when complimented sufficiently by each other. It is the natural balance of functioning government in a just society.

This is the founding vision. This is the government created by and the society enabled by the US Constitution. The founding project was, indeed, a perusal and debate on the first principles of government as gleaned from the light of human experience over history, but it was tempered and forged by the lamp of experience in the events of the founding itself.

Detractors may say that the idea of a founding vision or assertion of such a thing as founding or constitutional values is incomprehensible given the disagreements at the time and continued disagreements by historians and political theorists who study the American founding. But we can assert a vision and we can identify its values by considering what came of the deliberations of the time and which aspects of the American Republic’s governing framework and of America’s constitutional culture have stood the test of time.

Justin Stapley received his Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Utah Valley University, with emphases in political philosophy, public law, American history, and constitutional studies. He is the Founding and Executive Director of the Freemen Foundation as well as Editor in Chief of the Freemen News-Letter. @JustinWStapley