Reimagining the Social Contract

The social contract is neither a tool to enforce legislation restricting natural rights nor is it a vague consideration that has no true bearing in how government functions.

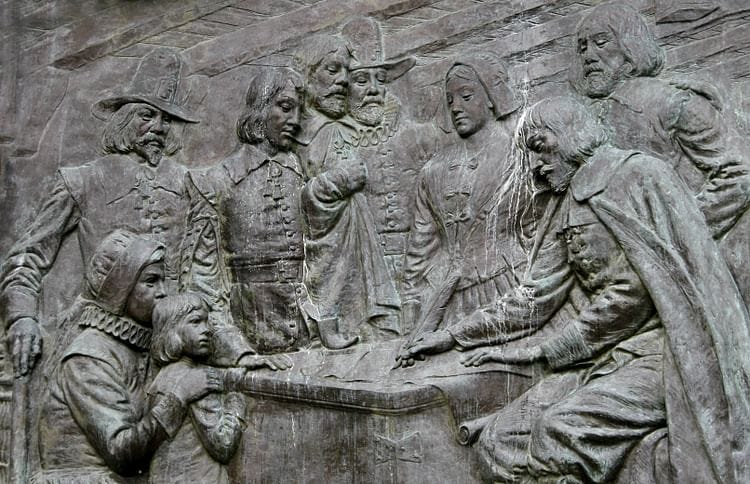

On November 11, 1620, something remarkable happened. Religious dissidents who had sailed to a new world put into practice theories that would spark a revolution in societal governance over the next 200 years. A new style of agreement between free men was born, with its roots in the Magna Carta 400 years before. With it came a historical record that would give birth to the most virtuous and free nation in the world: the United States of America.

On that fateful day in 1620, the Pilgrims signed the Mayflower Compact. The free men of the Mayflower, fleeing persecution in England, needed a set of rules to govern the new society of Plymouth. They offered up a set of rules for people to live by. It would also prove the theories of such great men as Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau decades later. The Mayflower Compact would serve as an early example of what was later dubbed “the social contract.”

The theories born out of these men’s work has become something of a slander in modern society. Many people, on both sides of the aisle, grossly misrepresent these theories. In this article, I will provide my own theory on what the so-called “social contract” actually says and discuss its misuse in recent political discussions. To do so, we must first look at where social contract theory began.

Before the Age of Enlightenment, the predominant theory of governance in both Europe and Asia was a concept that has come to be known as the “divine right” theory. The concept goes something like this: as a member of some ruling family, the king or queen has been born into power via divine intervention, and, as such, their right to rule should remain unquestioned and absolute.

The most famous European proponent of this theory was Louis XIV, a king renowned for his belief in absolutism. In China, they called this theory the “Mandate of Heaven.” While this was certainly a step up from the force theory of government, the divine right theory often terminated in a despotic king or queen grinding away at the rights of the people with impunity, as there was no philosophical justification for changing rulers.

In China, they partially remedied this problem with the “Mandate of Heaven” by providing a backdoor legitimacy to revolt by saying that a new dynasty could replace any dynasty that had “lost” the Mandate. However, the revocation of the Mandate only came after and through the great suffering of the people. This did little to help the cause of the masses or the individual.

By the time of the Pilgrims, this thinking had begun to change. The success of the Magna Carta had shown the men of England that there were limits to what a king could do. These Puritans, who left everything they had in England behind to begin anew, understood that the government did not magically spring from the hand of God; it was born out of an understanding amongst the people.

More importantly, though, they knew that for a society to function properly, it needed to have an agreement outside of governmental structures because governments were apt to abuse their power if given the opportunity.

This thinking would be reinforced later in the 17th and 18th centuries by such thinkers as Thomas Hobbes and Rousseau. In his great work The Leviathan, though not using the term itself, Hobbes describes the social contract as a situation in which man gives up some of his natural rights to gain some security, which an all-powerful government would then enforce.

Hobbes imagined that every man was, in his “state of nature,” entitled to everything. He posited that in the absence of government. I have a right to steal your food, just as you have a right to steal mine. However, by entering into an unspoken contract with the rest of society, we as civilized people agree to give up some of those natural rights. While his opinion on government was deeply flawed, Hobbes was correct in saying that a society does not have to explicitly write out a social contract for it to exist.

Locke comes closer to my own definition of the social contract in his suppositions on the subject. His theory on natural rights was much more correct than that of Hobbes. According to Locke, a natural right was the right to operate without the interference of other men or government, so long as that operation did not interfere with other people’s exercise of that same right.

According to Locke, the only right given up when entering this social contract was the right to take justice into your own hands. Instead of “eye for an eye” justice, a society forms government to distribute justice at the hands of the community at large. Locke, however, still tied the social contract to the operation of governmental power in his thinking.

The term “social contract” was not coined until the work of Jacques Rousseau in 1762. Rousseau’s arguments for the social contract were exemplary in their insight into the history of the human condition. Rousseau argues that as humanity has progressed, social and governmental institutions have grown up that have restricted the rights that humans in nature are born with. Therefore, he concludes, it is the purpose of the government, with the will of the majority at its backing, to restore those rights that the various institutions in our lives have restricted.

The most notable contribution to social contract theory that Rousseau posits, I believe, is his conception of duties that are reciprocal to the natural rights we as free people have.

Before I posit my own social contract theory, I would like to clarify where I believe these great men went wrong. In each of their examinations on the subject, these men came to one similar conclusion that I believe is flawed: that the government necessarily arises from the social contract and, as such, is in charge of enforcing its provisions.

While I will not deny that the government is granted authority via popular sovereignty, I do not believe this is the same mechanism as the social contract. Popularly elected governments have, since their inception, been prone to the denial of natural rights to some class of citizen or another, often with the backing of a majority. To entrust the government with enforcing the social contract, then, seems dangerous in my mind.

That is not to say these men got it all wrong. As noted before, Hobbes was correct in saying a society need not write the contract down to be effective. Locke was correct in assuming the contract arose out of a need to ensure that each man’s natural rights were protected and ensured by society at large. And Rousseau contributed the crux of my definition by supposing with each natural right comes a related “natural duty,” so to speak.

The social contract, then, can be stated as such: an agreement, whether written or unwritten, by members of society at large to both govern the protection of natural rights and the enforcement of natural duties.

This theory does not necessarily tie to governmental action, although it often falls to the government to protect a man’s natural rights. It also does not justify all governmental actions.

As I stated at the beginning of this article, too often, the term “social contract” is thrown around by both sides of the political spectrum as a derogatory term.

On the left, it is used to justify burdensome laws passed by the federal government. You often hear people justify higher taxes on the rich or Social Security, for example, by stating that as a citizen of this country, you have agreed to the social contract that justifies these positions. This is patently false. The social contract is not a tool to enforce legislation restricting a man’s natural rights.

On the right, many reject the idea of a social contract outright, allowing them to justify whatever behavior they see fit. This, too, is wrong. As a member of society, the expectation is that you will act in certain acceptable ways. That does not mean you have to act that way, via governmental action. It only means you should.

The social contract can change based upon societal acceptance of certain practices. Governmental action, too, can accept or outlaw certain practices that the social contract deems uncouth or acceptable.

Good examples of these concepts are interracial marriage and marijuana usage. In the former case, the government rightly made it legal long before society accepted it. In the latter, the government continues to wrongly outlaw its usage even as society accepts it more and more.

Too often, we look at the world in terms of politics and what is legal or illegal. In doing so, we forget that society and government are not the same things and that we should not treat them as the same thing. I have tried to redraw that distinction in reimagining the social contract. I hope you will agree with me.

“ While his opinion on government was deeply flawed, Hobbes was correct in saying that a society does not have to explicitly write out a social contract for it to exist.”

Exactly. People don’t seem to understand this today. Many also argue that if Locke or Hobbes or Rousseau did not exactly describe what life was actually like for prehistoric tribes, their theories must fall apart completely. But natural rights don’t stop existing because Locke’s state of nature did not comport exactly with the actual state of nature. That was never the point of positing a state of nature.

“ The theories born out of these men’s work has become something of a slander in modern society. Many people, on both sides of the aisle, grossly misrepresent these theories.”

Yes. We have grossly oversimplified these ideas in modern education and teach our children a bastardized version that is easy to straw man.

“ Locke comes closer to my own definition of the social contract in his suppositions on the subject”

Me too.

“ As noted before, Hobbes was correct in saying a society need not write the contract down to be effective. Locke was correct in assuming the contract arose out of a need to ensure that each man’s natural rights were protected and ensured by society at large. And Rousseau contributed the crux of my definition by supposing with each natural right comes a related “natural duty,” so to speak.”

It might be semantic, but I think I’d disagree on the idea of natural duty. I think God gives man natural duties. And a social contract necessarily implies them. But in a state of nature I’m not sure they exist in the same way that property or self-defense do. I could be wrong. I’ll have to mull that question. I suppose I’d say the strong have a natural duty to protect the weak, so perhaps you’re right.

“ In doing so, we forget that society and government are not the same things and that we should not treat them as the same thing.”

Absolutely agree with that. And on marijuana and interracial marriage.

Tip for the future: you don’t need to end by saying that you hope we agree with you. That’s implied by the fact that you’re making an argument and trying to convince us of your position.