John Locke and the Ruckus in the Harbor

The spiritual dimension of the taxation issue at the core of the Boston Tea Party.

Framing the Boston Tea Party with a spiritual dimension must be done carefully. That is to say, behind the level on which the concepts of ownership, property, and justice take prominence is a level on which the imago dei status of the human being must be central, but that must be argued convincingly. A critical mass of people has to be persuaded that that centrality is essential for the argument that taxation requires representation to have moral weight.

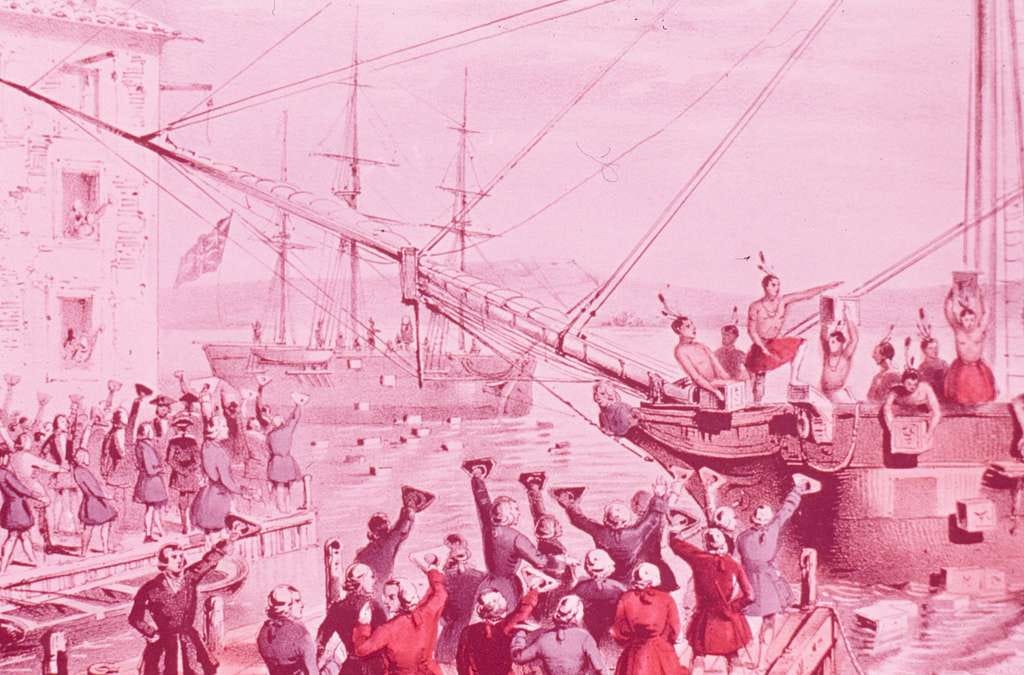

What actually happened on December 16, 1773, when the perpetrators headed from the Old South Meeting House to the ships in Boston Harbor, was pretty clearly a mob action. The Sons of Liberty, the organizing group, was a rather rowdy bunch, fond of meeting in taverns and burning public figures in effigy. They knew enough about the relationship between the state, the individual, and the question of what belongs to whom on a gut level to be motivated to stage their events and, by the time the Revolution broke out, expand their network of loosely organized chapters up and down the eastern seaboard.

But the groundwork had been laid in the ideas fleshed out in Chapter 5 of John Locke’s 1690 work Second Treatise on Civil Government.

One noteworthy aspect of that work is that Locke refers to God more than was characteristic for him. He predicates what he has to say about appropriating objects found in nature for productive use by asserting that the human being owns himself, as is befitting a creature imbued with free will. By inference, what the individual does with that self is his own as well.

Locke also shows that money is more than a lifeless medium of exchange for use in purely material transactions. Money allows two individuals or groups thereof to arrive at that thing that is so exceedingly rare in human affairs: agreement. After ownership of the natural objects of the world has been established, money makes possible the gravitation of those things to situations that are most inclined to enhance everyone’s well-being. Person A has a surplus of, say, corn grown on his land, but that surplus is going to have value to Person B, who owns a mill, that would not even occur to Person A until he’s approached about it. After the transaction, Person A’s realm of possibility for improving his lot is greatly expanded. He can spend or invest the money he’s gained in any number of ways.

It’s from the elegance of that scenario that great minds are motivated to consider how to best guarantee that no entity overrides the agreement. How shall we protect not the safety of Persons A and B and their corn and money, as well as ensure that the value of the corn isn’t distorted by outside forces?

Taxation is as old as the notion of government itself. It wasn’t until Locke and thinkers in his wake woke people up to the notion of individual sovereignty and the necessity of volition in economic activity, however, that anyone had much of a framework beyond brute force for talking about ownership and exchange.

By the 18th Century, we in the West were well on our way to being able to explain why letting the individual keep and use as he sees fit what belongs to him is right and interfering with that relationship between person and property is wrong.

The Sons of Liberty, as individuals, no doubt had varying degrees of understanding of this beyond the instinctual. But when a reservoir of outrage at having their freedom of economic choice diminished by an entity legitimized by a monopoly on the use of force reached a tipping point, instinct was enough.

They’d had it with impositions like the Stamp Act and the Townsend Acts. The British Parliament clearly underestimated the outrage, as would be later demonstrated by the Intolerable Acts passed in response to the Tea Party, which would further inflame the situation in Boston, leading to Concord and Lexington.

The reason the Chinese product that the East India Company was bringing into the colonies was cheaper than any other tea on the market was that Parliament was engaging in funny business using the tax code. The government had effectively set itself up as the only game in town for those who liked to sip tea.

What heady times those were. There were voices in Britain, such as Adam Smith and Edmund Burke, who upheld the notion of individual sovereignty, but it fell to more rough-hewn colonists on the Atlantic’s western shore to move the needle, to create the space whereby a people might determine how best to guarantee and maximize liberty in the way it organized itself into a society embarked on a novel form of government.

Barney Quick is an Adjunct Professor teaching Jazz and Rock & Roll History at Indiana University Columbus. He received his Bachelor’s degree in English and Literature from Wabash College and his Master’s degree in History from Butler University. @Penandguitar