Liberty-mindedness Does Not Automatically Equate Isolationism

It was Jefferson who advocated for American support for the French Revolution. It was Madison and his supporters who were termed the original War Hawks as they advocated for war against Britain.

Ever since the rise of the modern conservative movement, there has been an open wound of conflict between what can be termed neoconservatism and paleoconservatism.

On the one side are those who advocate for American leadership and engagement in the world. On the other are those who advocate for disengagement and avoidance of global entanglements. When the Berlin Wall fell and the threat of global communism vanished from geopolitical reality, this discord only widened.

Neoconservatism has generally been espoused by conservatives who are traditionalists, centrists, and moderates open to some progressive government. Paleoconservatives have generally been libertarians or nationalists.

It, therefore, is quite a shock to some when they find liberty-minded conservatives like myself and Liberty Hawk contributor Scott Howard advocating for America’s energetic role in the world and sometimes even for military intervention.

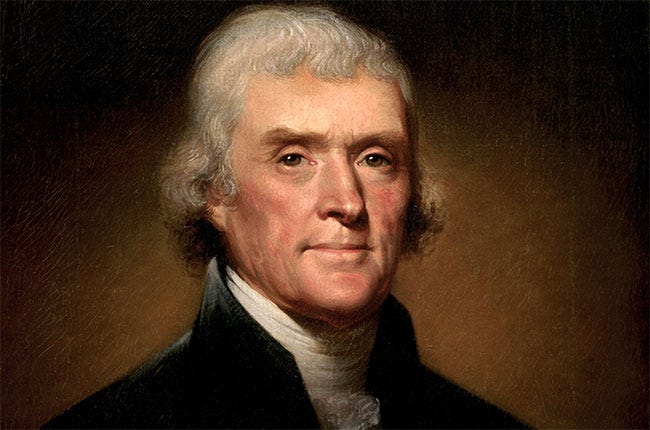

The connection between isolationist and libertarian tendencies is so ingrained in people’s minds, their reaction to our stances often assumes some underlying hypocrisy or intellectual inconsistency. And yet, Scott and I are quite consistent in how we follow the traditions of Jefferson and Madison.

It may be difficult for some to shed the mechanics of our modern politics and grasp the factions and issues of the early American Republic.

Alexander Hamilton and his Federalist Party were the advocates for larger and more involved government in that time period. It was Hamilton who established a national bank and argued for an increase in the debt to establish credit for the new nation.

It was John Adams, also a federalist, who signed the alien and sedition acts, one of the worst violations of rights passed by Congress. And yet, it was the Federalist Party and its greatest ally, George Washington, who stood most solidly in favor of isolationism.

On the other end of the spectrum were Jefferson, Madison, and their Republican Party. The early Republican Party was the party of limited government and of the rights of individuals.

When Jefferson ran against Adams for the presidency, he called it the second revolution, believing his election would solidify the values of the first revolution in the young republic. And yet, it was Jefferson who advocated for American involvement and support for the French Revolution. It was Madison and his supporters who were termed the original War Hawks as they advocated for war against the British.

At heart of the question between an energetic foreign policy and isolationism isn’t support for liberty or openness to big government, it is whether liberty is viewed as a global concern or only a national concern.

Modern conservatives who deride their opponents as globalists may be surprised to realize that much of Jefferson’s rhetoric in the Declaration of Independence was “globalist”. He didn’t write to King George declaring their duty to fight for their rights as Englishmen. He wrote about the rights of all men.

One of Jefferson’s famous quotes is, “I have sworn upon the altar of god eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.”

In fact, Jefferson was so supportive of the French Revolution that Washington’s position on the matter was a major part of Jefferson’s decision to resign as Secretary of State. Jefferson never spoke to Washington again and became an enemy of John Adams for many years.

So, while liberty-minded conservatives such as Scott and myself get a lot of flack for advocating for strong American leadership and a decisive role in the world’s affairs, our stance still remains grounded in liberty with pragmatic consideration of the world’s realities.

I leave you with two final points.

First, we are inheritors of the Jefferson view: that liberty threatened anywhere is liberty threatened everywhere. Divorced from a purely nationalist consideration of liberty, we see the American Revolution as one that continues, both within and without America’s shores.

We find common cause with freedom fighters the world over. The Hong Kongers, the Venezualans, the Kurdish Peshmerga; they are not Americans but they are just as much our brothers and sisters in the fight for liberty.

Second, we recognize the realities of the modern era. The globalist/nationalist debate is largely an abstract debate and divorced from reality. The world is smaller than it used to be. The vast and intricate interconnection of nations and peoples is a geopolitical fact.

The butterfly effect is very real. Instability in any region of the world threatens America’s interests. Pretending that we can retreat from the world without major consequences reaching our own shores is to put our head in the sand.