The Case for Citizens' Assemblies

Finding the will of the people on abortion after Dobbs.

The permissibility of abortion, and the limitations upon it, are to be resolved like most important questions in our democracy: by citizens trying to persuade one another and then voting.

-Antonin Scalia, Dissent to Planned Parenthood v. Casey

The U.S. Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) has returned the issue of abortion to the people. As Justice Alito wrote for the majority, “Abortion presents a profound moral question. The Constitution does not prohibit the citizens of each State from regulating or prohibiting abortion. Roe and Casey arrogated that authority. We now overrule those decisions and return that authority to the people and their elected representatives.”

This was the culmination of a half-century struggle by critics of Roe v. Wade (1973), who have long declared it to be an illegitimate usurpation by the Court of the people’s rightful authority. By long-standing principles of American constitutional law, the people have authority to enact laws concerning health, safety, welfare, and morals at the state or local level without interference by the Supreme Court unless the Constitution (or federal laws) protects rights that such laws violate.

According to critics of Roe, the right of a woman to choose an abortion is not protected by the Constitution. Therefore, they contend, the Court in Roe illegitimately exercised “raw judicial power” by imposing its own views on the people and stripping them of their sovereign authority.

Thus, pro-life critics of Roe have long advocated for two things. First and foremost, they have sought state protection for the lives of embryos and/or fetuses. Second, they, along with pro-choice critics of Roe, have championed letting the people decide whether and when abortion should be banned or restricted.

This question is extremely difficult because, among other things, it requires assessing and weighing conflicting (and, in some cases, contested) human rights claims: women’s rights to health, safety, and bodily autonomy, on the one hand, and the right to life of embryos and fetuses, on the other.

In his Dobbs concurrence, Justice Kavanaugh pointed out that the question of how to resolve these conflicting and weighty “interests” is difficult and something about which there is much good faith disagreement. For this reason, if given the chance, the people of different states would likely answer it differently.

This, Justice Kavanaugh and many others have contended, is a compelling reason to not set a national standard on abortion law. But if there is to be a national standard, it should be set by the people, presumably through their representatives in Congress or by following the constitutional amendment process. In either case, they’ve argued, as demonstrative in the opening Scalia quote, that a national standard on abortion most certainly should not be set by the U.S. Supreme Court.

So, in sum, critics of Roe have long contended—and the Supreme Court has now declared—that there are vital conflicting interests and rights at stake with abortion; that the U.S. Constitution is silent on how those interests and rights should be weighed and balanced; and that in such a case, only the people, through a proper representative process, have authority to decide the issue. (Of important note, however, the majority opinion appears to leave open the possibility that a fetal right to life could be found in the 14th Amendment, notwithstanding Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence. Erika Bachiochi has recently contributed to the public discourse arguing for embryonic/fetal rights protected by the 14th Amendment).

It is important to highlight that this resolution is consistent with at least three cherished American traditions.

First, it is consistent with the American human rights (or natural rights) tradition, which holds that laws and institutions are just insofar as they secure human/natural rights, including, but not limited to, the rights to life and liberty.

Second, it is consistent with the American tradition of popular sovereignty, which holds that the people are the highest authority in the land. Even if rights (and attendant duties) derive from “the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God,” it is “We the People” who have ultimate earthly authority to, among other things, (a) resolve disputes over what those rights are and (b) decide which laws and institutions are fit and proper for securing them.

Third, it is consistent with the timeless American aspiration for a just system of representative government: one in which all citizens—or at least those citizens who are affected by laws and public policies—have their rights, interests, and opinions properly represented in the process by which laws and policies are made. (For example, in his Full Vindication essay [1774], Alexander Hamilton expressed common sentiment when he applied the principle of representation to all laws, not just taxes: “The only distinction between freedom and slavery consists in this: In the former state a man is governed by the laws to which he has given his consent, either in person or by his representative; in the latter, he is governed by the will of another. In the one case, his life and property are his own; in the other, they depend upon the pleasure of his master.”)

Thus, in the wake of Dobbs, it now falls upon the people to decide abortion laws at the state and/or federal level. Abortion laws can take several forms, including legislative statutes, referenda, citizen initiatives, and/or constitutional amendments. But regardless of what type of law is under consideration, a fundamental question must be decided: how should the will of the people on abortion be determined and declared?

The Process for Declaring the Will of the People on Abortion Should be Representative and Deliberative

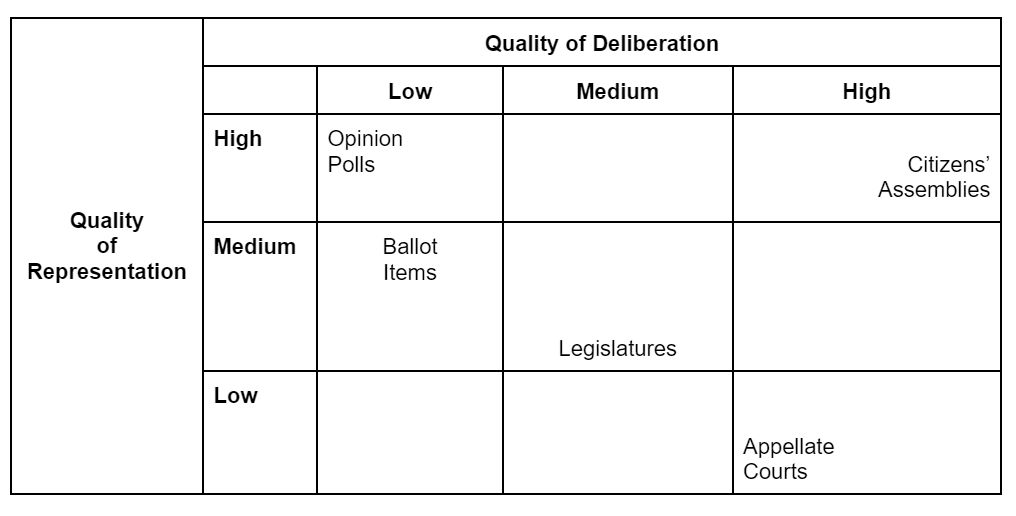

I argue that any process worthy of the task of declaring the will of the people on abortion must meet at least two conditions: it must be representative and it must be deliberative.

First, the process needs to be based on the majority will of a decision-making body that properly represents the people. For the people to be properly represented, there should be proportional representation of all conceivably relevant demographic traits of the population, including sex, religion, race, education, rural vs. urban residence, socioeconomic status, and political party identification. (A representative process could alternatively mean weighing those most affected by abortion laws more heavily. Here, a case can be made that a representative process for declaring the popular will on abortion should be composed disproportionately, if not entirely, by women, since women are the ones most affected by abortion laws).

It should also mean proportional representation of citizens’ preconceptions on the issue of abortion. For example, if, prior to deliberation, 15% of citizens express support for legal abortion on demand at all stages of pregnancy and 15% express support for legal bans on abortion with no exceptions beginning at conception, then the decision-making body should include a sample in which those preconceptions are proportionally represented.

Second, the process needs to be deliberative. Well-conducted opinion polls are based on a representative sample of a population, and so they would be adequate for ascertaining the will of the people if representativeness were the only criterion. However, for an issue as important as abortion, it is necessary to make sure citizens have adequate opportunity to become well-informed and to try to persuade each other of the justness of their views. For this reason, the process of ascertaining the will of the people on abortion needs to be deliberative, as well as representative.

To be sure, at the end of the deliberative process, the matter will need to be put to a vote, and some views will be outvoted. But having the majority’s will prevail after a proper deliberative process among a representative group of citizens is the essence of what popular sovereignty demands. Or, as Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in Planned Parenthood vs. Casey, issues surrounding abortion, “like most important questions in our democracy,” should be resolved “by citizens trying to persuade one another and then voting.”

A process that assures, prior to voting, that a representative sample of citizens are enabled to become well-informed and to seek to persuade one another is the process most fit and proper for declaring the will of the people on a matter as important as abortion.

A Citizens' Assembly is the Most Representative and Deliberative Method for Declaring the Will of the People on Abortion

I contend that a deliberative Citizens' Assembly is the approach to declaring the will of the people on abortion that best meets the two criteria of representation and deliberation.

Citizens’ assemblies can take many forms, but they all have several features in common. They are composed of a representative sampling of citizens, usually drawn by a process of random selection akin to those which are used for public opinion polling and jury selection. Also, they are deliberative in that the citizen participants, prior to voting on resolutions, are provided an opportunity to become accurately informed, to hear multiple perspectives, and to share their views and perspectives with each other.

Invariably, this involves facilitators providing participants with a common set of verified facts and allowing participants to consult with experts. And participants are allowed and encouraged to discuss and debate with each other following the norms of civil discourse and according to clearly defined rules. Again, the specifics of Citizen Assembly designs can vary, but they all involve those core elements.

A promising model for a Citizens’ Assembly on abortion for Americans to consider is the one that convened in Ireland in 2016-2017 to deliberate on the nation’s abortion laws. This assembly, which was established by legislative resolution, was composed of 99 citizens carefully selected to assure they were demographically representative.

(Critics have pointed to potential education/class disparities created by the relatively high personal cost and inconvenience of participating in the Assembly. This can and should be avoided in an American Citizens’ Assembly by offering generous compensation to participants. The benefit of Assemblies is diffuse, and the financial burden of funding them should be as well. The burden should not be concentrated upon those who are already sacrificing time to serve on behalf of the people. Instead, the burden should be shared by others, either through small tax contributions or by donations from philanthropists and civil society groups.)

In their deliberations, which were spread out over five separate sessions, citizens were provided with well-vetted factual information, exposed to the viewpoints offered by 25 experts, and able to read 300 comments submitted by fellow citizens who were not members of the assembly. The assembly’s primary recommendations formed the basis of the referendum bill that the people of Ireland approved in 2018.

In the United States, the people in different states (or at the national level) could try various models for their Citizens’ Assemblies. Establishment of Assemblies by legislative resolution, as in the Ireland example, is probably optimal since it would signal a willingness of legislatures to closely follow Assemblies’ declarations of popular will.

But even an independently established Assembly could be of great value since it would provide an authoritative account of the will of the people upon which bills could be modeled and against which they could be measured.

Similarly, the recommendations from Citizens’ Assemblies need not result in referendum bills the way Ireland’s did. Instead, Assemblies’ recommendations could become model legislation for legislatures to craft into bills or proposed constitutional amendments sent out for popular or legislative ratification.

And a Citizens’ Assembly could be larger or smaller, increase or decrease the number of invited experts, expand or reduce the criteria for determining relevant expertise, provide alternative channels for involvements of citizens outside the Assembly, and so on. There are endless varieties of models to consider.

I contend there are strong reasons to favor the use of Citizens’ Assemblies for determining and declaring the popular will. Assemblies are not perfect, but, of course, all we can ask for is the best feasible option. So, let’s now turn to why I argue that a deliberative Citizens' Assembly is the best feasible option for declaring the will of the people compared to the three leading contenders: appellate courts, legislatures, and direct popular vote.

A Citizens' Assembly is Better Suited than an Appellate Court for Deliberating on Abortion Policy

A Citizens' Assembly would be better suited for addressing abortion issues than the venue Americans have relied upon most for the past half-century: the Supreme Court.

Of course, the Supreme Court and its state high court counterparts do not claim to be venues for declaring the will of the people, except for the people’s “higher will” as reflected in constitutions. Still, it is worth noting that a Citizens’ Assembly would, of course, be more representative than the Supreme Court, which is not only unelected, but is also vastly unrepresentative of the U.S. population on education, income, gender, religion, and race.

Although state courts typically are composed of elected judges and can be less unrepresentative of the people than the U.S. Supreme Court, they are still much less representative than a Citizens’ Assembly and, indeed, American legislatures.

And in recent years, the U.S. Supreme Court and many state high courts have become ideologically unrepresentative of the people as well, at least if we go by justices’ and judges’ known partisan identifications and/or the party of the elected branch that selected them.

And for abortion in particular, it is highly relevant that judges are now typically appointed only after being vetted by abortion activists with views that are far from representative of the national majority (at least according to opinion polls).

Lack of representativeness is an obvious limitation of courts as decision-making bodies. But even without taking that into account, I contend that an appellate court like the U.S. Supreme Court is an inferior venue for deliberation on abortion than a Citizens' Assembly would be. This claim is somewhat controversial since many scholars and American citizens view the U.S. Supreme Court as a forum of high principle and superior deliberation.

However, as Jeremy Waldron has long argued, courts are poorly constituted for addressing the complexity of moral rights claims because, among other things, they are bound by legal conventions, confined to the specifics of case facts, and are forced to limit their inquiries into what the positive law (rather than, say, one’s best understanding of justice) requires, allows or prohibits.

Due to the Court’s limited role and associated norms, Justices generally do not explicitly state or defend judgments about the ethical issues at stake with abortion when justifying their decisions even if those judgments influence their decisions. Citizens’ Assemblies do not face these limitations. An Assembly would allow for openly, directly, and honestly addressing the major moral issues associated with abortion.

Indeed, our public discourse has been so influenced by the legal-constitutional debate—as well as by polarizing rhetoric propagated by activists and the political parties they influence—that the Assembly would likely provide an opportunity for the citizen participants to hear for the first time the best arguments made by all sides of the debate. Thus, a Citizens' Assembly would avoid the shortcomings of the Court as a venue for deliberating on the issues at stake in abortion and may well help mitigate some of the damage to our national discourse created by those shortcomings.

A Citizens' Assembly is Better Suited than a Legislature for Declaring the Will of the People on Abortion

Compared to Citizens’ Assemblies, legislatures also fall short on our two criteria of representation and deliberation. Let’s consider each in turn.

Although American legislatures are certainly more representative than courts, they are also much less representative than a Citizens’ Assembly. Most states operate under unified party government. Majority parties in such situations often claim to represent a majority of citizens, but their platforms and enacted policies are often out of step with majority will (at least according to opinion polls). This is often because parties can win majority control of government without winning a majority of statewide votes.

Geographic sorting along partisan and ideological lines contributes to unrepresentative party government in many states and in the U.S. Senate. People drawn to the Democratic Party are increasingly clustered in urban areas and those drawn to the Republican party typically comprise strong majorities in the more numerous rural districts. Under this state of affairs and our current single-member district election system, Democrats often win less than a majority of seats in state legislatures (and the U.S. Senate) even when they win a majority of statewide (or nationwide) votes. But of course, even when Democrats win a majority of seats, they, for most of the reasons stated above, typically cannot truthfully claim to represent a majority of citizens.

And, lest we forget, there are also many citizens who don’t vote. So even a majority of voters is not equivalent to a majority of citizens.

Furthermore, specific elements of a party's platform are often not supported by significant percentages of those who vote for the party. Voters often vote for a party simply because they reject the other party more and not because they support all or even most specific aspects of the party’s platform. For these reasons, a majority party typically cannot justifiably claim that any specific item from its platform represents the will of the people.

Furthermore, in every state except Nevada, women hold well under 50% of the seats in legislative chambers despite comprising a slight majority of the population nationally and in every state. When it comes to declaring the popular will on abortion laws, a plausible case can be made that women should be overrepresented in the process due to the fact that abortion laws disproportionately impact them. That can be debated, but no one can plausibly argue that women should be underrepresented in the process.

Now, to be clear, the claim here is not that contemporary American legislatures are somehow “illegitimate” or that they could not be considerably less representative than they are now. For all of the criticisms (many of which are undoubtedly well-founded) of the current system, it is important to note that the U.S. is still rated among the 30 most democratic countries in the world by most expert appraisals. However, warnings of a trend toward something much less representative—toward electoral autocracy, for example—is highly worrisome. Autocracy thrives under conditions of mutual intoleration, so claims of illegitimacy should never be made lightly and are always dangerous for supporters of free representative/democratic government. Specifically, we should respect majority parties that have gained power by following the rules of the game and should recognize their claims of considerable legitimacy.

The claim here is simply that, since the rules of the game that they are currently following do not guarantee anything that could be considered close to proportionate representation of citizens, contemporary American legislatures do not have the best claim to representing the will of the people.

Our goal is to find the best feasible way for declaring the true will of the people on the vitally important issue of abortion. To achieve this, we need to hear the voices of a representative sample of citizens, and a well-constituted Citizens’ Assembly would clearly be superior to any existing American legislature for that purpose.

American legislatures have also increasingly shown an unwillingness to engage in meaningful deliberation. In Congress, bipartisan compromise is often essential for getting things done, and this can create an occasion for a modest amount of deliberation among pivotal members. But this is a far cry from the rigorous deliberation Citizens’ Assemblies engage in. And with the abandonment of regular order, the deliberation facilitated by committee work has had a diminished impact on the process.

In the states, bipartisan compromise is often unnecessary, which creates even less occasion for deliberation than in Congress. As a result, the party in power in most American legislatures today can seek to enact laws without accommodating the opposing party’s position in any significant way or allowing them to seek to persuade them of the merits of their position. Indeed, majority parties are more likely to accommodate the views of lobbyists and their own party’s activists than the views of members of the other party.

Given the poor state of public discourse on abortion and the absence of meaningful legislative deliberation, there is little reason to think abortion laws enacted by majority parties will be made with full awareness of, or due consideration given to, the best arguments made on all sides of the debate.

In general, polarization, and the factors causing it, are driving the trend toward unrepresentative legislatures that rarely, if ever, engage in meaningful deliberation. We are increasingly beset by what we now call pernicious (or negative) polarization and what James Madison called the “mischiefs of faction'': a condition in which our two major parties are “inflamed … with mutual animosity, and … [are] more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to co-operate for their common good.”

Until this trend is reversed, and a better system for electing representative legislatures is widely instituted, a well-constituted deliberative Citizens' Assembly will be a much more reliable venue than a legislature for ascertaining and declaring the will of the people on abortion.

It should be added that our current process of electing representatives also in no way resembles what Justice Scalia described as “... citizens trying to persuade one another and then voting.” The typical campaign—driven by emotion-laden propagandistic ads—is of even poorer deliberative quality than what occurs in our legislatures.

With only 10% of districts competitive, congressional politics is now more often about intraparty purity tests than about debating issues on which the two major parties disagree. And, regardless of how competitive an election is, if abortion policy is salient, the issue will most likely be covered by the campaigns in a way that actively discourages citizens from giving it the kind of thorough, reasoned consideration it requires.

Campaigns are much more likely to use half-truths (at best) and manipulation to mobilize voters than they are to facilitate a process in which citizens become accurately informed and are enabled to seek to persuade one another through honest discussion and debate. Rather than leading citizens to understand that abortion policy raises genuinely difficult moral questions on which there is much reasonable and good faith disagreement, campaigns find it more effective to play into citizens’ basest instincts by portraying abortion policy as a Manichean struggle between one’s own virtuous tribe and the other evil/dangerous tribe that must be defeated at all costs.

Until our electoral system and campaigns dramatically change, only a Citizens’ Assembly will create a forum for the kind of reasoned consideration of all sides that abortion policy deserves and demands.

A Citizens' Assembly is Better Suited than Direct Popular Vote for Declaring the Will of the People on Abortion

The final leading alternative to a deliberative Citizens' Assembly would be to simply put an abortion law on the ballot for an up or down popular vote. Once again, based on our criteria of representativeness and deliberation, there is strong reason to think this would be inferior to an Assembly.

First, the electorate for a popular ballot vote, while certainly more representative of the citizenry than legislatures, would still not be as representative as a well-constituted Citizens’ Assembly. Due to discrepancies in voter turnout, electorates for ballot initiatives (and elections in general) typically are not representative of the people as a whole. So, a majority vote alone would not be a good indicator of the people’s views on the ballot item.

Furthermore, if the ballot item does not derive from the recommendation of something like a Citizens' Assembly, it is unlikely that even an affirmative vote could be taken to mean the ballot item is a good approximation of the will of voters on abortion. If only allowed an up or down vote on the item, an affirmative vote could only be taken to mean that the voters think the new law is better than the status quo. But it’s quite possible to improve on the status quo while falling far short of the actual will of the voters.

Second, if citizens vote without the benefit of a deliberative process prior to the vote, many citizens’ decisions will be based on views that are not adequately informed or subjected to adequate scrutiny.

Laboratory and field experiments have demonstrated that when citizens participate in citizen assemblies and deliberative polls, they often change their minds on issues. This means there is reason to think that how citizens typically respond to opinion polls or vote in elections is different from how they would respond or vote if first given the chance to become better informed and to engage in discussions with citizens who have different viewpoints.

For many purposes, voting on ballot items (and candidates) is an adequate way to gauge the sense of the people. But when it comes to something as morally important and difficult as abortion, there is simply no substitute for engaging in a deliberative process prior to voting if the goal is to declare the true will of the people.

Summary of the Quality of Alternative Processes for Declaring the Will of the People on Abortion

Responses to Anticipated Objections

“This seems like a radical departure from the American way of doing things.”

Actually, deliberative Citizens’ Assemblies are very much in keeping with traditional American practices.

Consider, for example, the Ratifying Conventions that voted to ratify the U.S. Constitution in 1787-1788. The point of those Conventions was to assure the people were well represented while facilitating a process of rigorous deliberation.

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia could have asked the state legislatures to ratify the Constitution, but they had good reason to think the legislatures would not accurately represent the will of the people on the question at hand. And they could have put it up for direct popular vote, but they knew doing so would not have allowed for proper deliberation.

The framers believed the authority of the Constitution would derive, not from their own wisdom, but rather from the fact that the people consented to it through “reflection and choice” rather than having it imposed on them by “accident and force.” They knew this meant they needed popular Ratifying Conventions that were more representative than state legislatures and more deliberative than a direct popular vote.

The case for Citizens’ Assemblies today is essentially the same, except that our contemporary standards for the quality of representation are higher than theirs and the details of the deliberative process would, of course, be different.

Likewise, in Article V of the U.S. Constitution, the Founders provided ratification by popular Ratifying Conventions as an option for amending the Constitution. Article V reflects the Founders’ anticipation that, at least in some cases, popularly elected Ratifying Conventions would be a better venue than legislatures for ascertaining the will of the people.

So far, 26 out of 27 amendments to the U.S. Constitution have gone through the legislative channel for ratification. But on one occasion, the ratification of the 21st Amendment, Ratifying Conventions proved to be the better route.

A Citizens’ Assembly would also serve a similar purpose as the constitutional rule in most states that constitutional amendments require support by a majority of voters on a statewide popular ballot to be ratified. The theory behind that procedural requirement is that constitutional amendments require direct consent by the sovereign people rather than by their elected representatives. That is, the establishment of the highest law in the land requires approval by the highest authority in the land, which is the people and not the legislature.

However, the discussion above has provided reason to think our state constitutions would do better by allowing (like Article V of the U.S. Constitution) or requiring ratification through deliberative Citizens’ Assemblies rather than ballot items. Such a method is both more representative and more deliberative than ratification via popular ballot.

Last but not least, a Citizens’ Assembly would share many qualities of one of the most vital institutions of American constitutional government: jury trials. Like a Citizens’ Assembly, juries are drawn randomly from the population in an effort to make them representative. And, like members of a Citizens’ Assembly, jurors deliberate before voting, sometimes for multiple days. Furthermore, jury trials are considered to be most important when the stakes for defendants are highest. If life and liberty are on the line—i.e., when defendants face the death penalty or long imprisonment—trial by jury is thought essential for due process. Life and liberty are also on the line with abortion laws. Thus, it seems something akin to a jury is similarly essential for assuring just decisions based on the considered judgment of the people.

“This sounds too expensive.”

This will be expensive. To get a representative sample, it is essential to compensate participants for the time they are asked to sacrifice. But other ways of deciding on abortion policy are expensive as well.

For example, it is expensive to spend money on campaigns in an effort to influence the composition of the Supreme Court. Also, efforts by activists trying to influence legislators and public opinion through advertising and propaganda are also expensive.

But money spent on Citizens’ Assemblies would result in something of greater value than all those other expenditures: an authoritative account of the sovereign will of the people. Disagreement over abortion by (the disproportionately represented) extremists on both sides of the issue has torn this country apart for nearly half a century. It seems well worth the expense to fund a process that is optimally designed for reaching a decision on abortion that is most reflective of the true will of the people.

I’d add that a successful effort at declaring the will of the people on abortion through Citizens’ Assemblies could go a long way toward restoring public faith in democracy and the potential for us to find depolarizing methods of self-governance. It’s hard to imagine an investment in our civic instructure that could have a more positive impact than that.

“How can we convince legislatures to establish Citizens’ Assemblies?”

Ideally, American legislatures, like in Ireland, will be keen on establishing Citizens’ Assemblies because they recognize the moral seriousness of the abortion issue and want an optimal procedure for gauging the will of the people.

But if they do not establish or even approve of such an Assembly, the people of a state can still establish one as a civil society initiative. Having a procedure for proclaiming the will of the people that any reasonable person would have to recognize as authoritative will serve as a yardstick against which to judge the quality of laws enacted by an uncooperative legislature.

It could also have an implicit or explicit influence on such legislatures, and possibly sway voters if abortion laws are put on ballots. So, legislatures, like in Ireland, may want to establish Citizens’ Assemblies because they are persuaded they would be beneficial. But even if they aren’t, Assemblies are still worth establishing independently as civil society endeavors.

“OK, then how can we do this as a civil society initiative?”

There should be widespread support for such an Assembly by civil society groups on all sides of the abortion debate and by groups that simply want to promote a healthier democracy and civil discourse.

Everyone should support it who believes abortion laws should properly be set in a manner that is in line with the will of the people. Anyone who thinks public opinion is not on their side should support such an Assembly because it would be their best opportunity to see public opinion shift in their direction. Anyone who thinks public opinion is on their side should support such an Assembly as an opportunity to demonstrate that public opinion is resilient even when subjected to full information and deliberative scrutiny.

The key would be to reach out to a diverse array of pro-life, pro-choice, and non-abortion groups and bring them on board. They must not be allowed to improperly influence the proceedings, but their support would be essential for legitimation and for drawing popular attention to the proceedings.

I should add that it will be essential that all major groups be involved in organizing and planning the Citizens’ Assemblies anyway, so that the process is widely (and rightfully) viewed as trustworthy. Those who are afraid of abortion laws that reflect the true will of the people (because they fear their position lacks majority support and believe they can impose their will without it) will see Citizens’ Assemblies as a threat.

It should be expected that they will do all they can to spread distrust in them and discredit the integrity of their proceedings. This must be guarded against from the beginning by constructing Citizens’ Assemblies transparently, with broad/diverse participation, and according to the known best practices for the design and conducting of such assemblies.

“Who knows how to run Citizens’ Assemblies?”

Here is a list of organizations that could be consulted for the creation and operation of Citizens’ Assemblies: Sorition Foundation, Deliberations.US, The People, Stanford Center for Deliberative Democracy, Voice of the People, University Maryland Program for Public Consultation, Center for Blue Democracy, Participedia, People Powered, UK’s Involve, The Co-Intelligence Institute, Deliberative Citizenship Initiative

“I don’t think the status of our fundamental legal rights should be subjected to majority approval. In a constitutional democracy, enumerated rights are supposed to limit the majority.”

Fundamental legal rights don’t just fall from the sky and are not self-enforcing. In the United States, constitutional rights have legal authority only insofar as they are based on the consent of the sovereign people. As a practical matter, this means every constitutional right is subject to revision and amendment by the people. Thus, constitutional rights require majority support (or at least acquiescence) if they are to be secure because no right is immune to constitutional amendment or disregard if a strong majority rejects it.

If a claimed legal right is strongly rejected by a majority of citizens, the only way it can be protected from violation by ordinary legislative majorities is if (1) those majorities are unrepresentative of, and unresponsive to, a majority of citizens or (2) the legislature is subordinated to the power of an unrepresentative/countermajoritarian institution, like a constitutional court. That is, if a right is protected from a majority that strongly opposes it, it must be because the system deviates from democracy in important ways.

Reliance on undemocratic institutions might be beneficial in certain circumstances, but it often makes the right insecure (in addition to all other inconveniences created from departing from democratic principles).

For example, believers in a human right to reproductive autonomy have just learned what can happen when an unrepresentative/countermajoritarian institution is relied upon to secure a contested human rights claim. That same institution can become staffed by those who reject the human rights claim. In this case, it was believers in a different, conflicting, and even more contested human rights claim (i.e., the right to life of embryos) who repudiated constitutionally protected reproductive rights.

If opinion polls are accurate—and I hasten to note that, even if they are, they most likely do not fully reflect what a Citizens’ Assembly would conclude after deliberation—proponents of reproductive rights would have been better served by securing those rights through a nationwide referendum (if such a thing were allowed in the U.S.) than by entrusting it to a countermajoritarian institution like the U.S. Supreme Court. Indeed, it is noteworthy that abortion rights have been secured in most Western European democracies through legislation or referendums, and not by constitutional courts.

Ultimately, as James Madison argued, the best security for a human right in a democratic/republican government is for it to become internalized as a norm by a strong majority of citizens. Trying to secure a right that is strongly rejected by the majority must require deviating from majority rule, which is always of questionable legitimacy at best.

I contend that the most proper way for proponents of a human right to win over the hearts and minds of the majority is through honest efforts at persuasion. Citizens’ Assemblies are especially well suited for facilitating a process of reason-giving and persuasion. Even though Assemblies include only a small sampling of the population, their holdings and public justifications can and should carry a lot of weight in the discourse among the broader public.

“I’ve heard Citizens’ Assemblies often fail. Why would this be different?”

This article nicely summarizes the reasons for “failure.” A couple of responses.

First, an Assembly should not necessarily be declared a failure if its recommendation does not become enacted into law. The main point of them is to establish an authoritative account of the will of the people and to provide an example to the public of what a representative and deliberative process can look like. The latter, in turn, can temper claims of an unrepresentative/non-deliberative legislature to have a mandate to enact its own will. And, as mentioned, it could influence the law even if the full recommendation is not implemented.

Second, there are known challenges to having a successful assembly, but an understanding of best practices is emerging. For example, how to get a truly representative sample is a challenge, but it is now understood that paying participants for their time goes a long way in resolving the issue. (This creates an additional problem of raising funds, but that’s hardly intractable in the U.S.)

It’s also illustrative that one of the best examples of a “successful” Assembly was the one that focused on abortion in Ireland. It is possible that the abortion issue has qualities about it that render it particularly amendable to consideration by a Citizens’ Assembly.

Appendix: A Preliminary List of Legal/Policy Questions for Citizens’ Assemblies to Address

- At what stage of pregnancy, if at all, should abortion be prohibited?

- If abortion is permitted at any stage of pregnancy, what restrictions, if any, should be placed on abortion during that stage?

- If abortion is prohibited at any stage of pregnancy, what exceptions, if any, should apply to the prohibition?

- Who will be held criminally liable for violating abortion laws? (Abortion providers? Women who seek abortions? Others? No one?)

- What practices should be allowed or prohibited for identifying, investigating, and prosecuting suspected violations of abortion laws?

- What should the punishment be for those found guilty of violating abortion laws?

- What, if any, laws and policies should be enacted (1) to mitigate the conditions that cause some women to seek abortions and/or (2) to render the decision to have a child more appealing and financially feasible for more women?

- What, if any, laws and policies should be enacted that assure it is safe and/or convenient for a woman to get an abortion if she decides she needs one?

- What should be done about the fact that the people of different states in Citizens’ Assemblies are likely to answer the above questions differently?

- Should a national standard, based on the recommendation of a national Citizens’ Assembly, be established by Congress (or through the amendment process)?

- If recommending a national standard, must all states accept it in its entirety? Or would it be like the Roe regime: a floor for rights above and beyond which states are free to offer greater protection? If so, which rights will make up the floor: the rights of pregnant women or the rights of embryos/fetuses?

- Alternatively, should we maintain the current post-Dobbs status quo of no national standard, with states free to enact whatever abortion laws they want?

- If states are allowed to enact different laws (either because of no national standard or a standard that is a floor for rights) how should the various federalism issues be resolved?

Michael Evans is a Senior Lecturer at Georgia State University. He received his BA in Philosophy, Politics, and Economy and his MA in Political Science from Western Washington University and received his PhD in Government and Politics from the University of Maryland. @USCivitas