To See the World Anew

Freedom, the Sermon on the Mount, and Lincoln’s Second Inaugural

This essay was adapted from and expands upon a sermon originally delivered by Kenly Stewart on February 12, 2023 ( Lincoln’s birthday) at his home parish, Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church, Clinton, NC. All scripture references come from the New Revised Standard Version unless otherwise noted.

If you choose, you can keep the commandments,

and to act faithfully is a matter of your own choice.

He has placed before you fire and water;

stretch out your hand for whichever you choose.

Before each person are life and death,

and whichever one chooses will be given.

For great is the wisdom of the Lord;

he is mighty in power and sees everything;

My home denomination, the Episcopal Church, along with many other Christian denominations, uses the Revised Common Lectionary. The lectionary provides us with our scripture readings for each Sunday's service. The Book of Common Prayer used by Episcopalians and other Anglicans as our primary liturgical guide includes four scripture readings for normal services. These readings are drawn from various parts of the Bible, with one reading from Hebrew scripture, one from the Psalms, one New Testament epistle, and, finally, a reading from one of the four Gospels.

When I preach, I like to anchor my sermons in the text of Holy Scripture, so I often reread a specific verse from one of that Sunday’s readings as a preface. Above is the Old Testament reading assigned on February 12, 2023. If you are a regular church attendee or avid Bible reader and don’t recognize the book listed above, do not fret. Depending on if one is Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish, and depending on the exact translation one reads, Sirach may not be found in your copy of the Bible at all.

For Christians, the debate about the canonical (official) status of Sirach has been ongoing for centuries. The debate reached its zenith in that minor family squabble called the Reformation. Henceforth, the majority of Protestants (along with most Jews) have denied Sirach’s authority, declaring it and other non-canonical books as apocryphal. For Catholic and Orthodox Christians, however, these books are considered deuterocanonical, or belonging to a secondary canon, and so are still considered scripture.

Living up to its famous designation as a middle way (via media) between Roman Catholics and Protestants, Anglicans have historically held a nuanced view of Sirach. The Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, originally produced in 1571 as a summarization of the central doctrines of Anglicanism, declare that “the Church doth read for example of life and instruction of manners,” deuterocanonical texts like Sirach, “but yet doth it not apply them to establish any doctrine.”

Regardless of its exact canonical status, since the time of the Early Church, Sirach has been recognized as a profound source of wisdom. Indeed, within the New Testament itself, the Holy Virgin Mary, Saint Paul, and yes, Jesus, quote from Sirach.

I wish more Christians (and non-Christians for that matter) drank from Sirach’s nourishing waters. Why do I hold Sirach in such high regard? Because, like all great sources of wisdom, when it produces answers, deeper questions almost immediately arise.

Take verses 15 and 16 from above:

He has placed before you fire and water;

stretch out your hand for whichever you choose.

Before each person are life and death,

and whichever one chooses will be given.

Fairly simple statements about free will, yet they can lead us to intense reflection on the very nature of freedom itself.

Freedom, especially in America, holds an almost sacred status. After all, this is the land of the free. In my home state of North Carolina, our license plates proudly declare we were “First in Freedom,” in honor of being the first state to call for complete independence from Great Britain. New Hampshire’s state motto, “Live free or die,” captures the quasi-religious status of freedom in our country most concisely. Only a non-American, one who has never visited this country, could read that motto as hyperbolic. For Americans, it is an obvious, dare I say, self-evident truth.

According to Sirach, and attested throughout Scripture, God granted humans the immense gift and responsibility of freedom, one which reflects God’s own free nature. After all, we are the creatures made in God’s own image.

But what do we mean by freedom? That’s an easy one. To quote the great philosopher Kenny Chesney, freedom is “no shoes, no shirts, no problems.” Laying on a beach, enjoying the breeze, watching the tide come in. Nobody telling you what to do. Nobody asking you to do something. No responsibilities. No external barriers of any kind stopping you from doing what you want.

Sounds nice, doesn’t it? Then again…maybe not.

Offering a more melancholic picture of freedom, Kris Kristofferson memorably sang, “Freedom’s just another word for nothin' left to lose.” But if one has “nothin’ left to lose,” then what does one have to live for? To strive for? To hope for?

Who is freer? The person with no job and no boss? Or the person who has meaningful, life-giving work, even with a boss? Who is freer? The single man crippled with loneliness? Or the man in a loving marriage? Surely, the married man has more responsibilities and certainly has, at times, someone telling him what to do. But does he not receive, in a deeper sense, a richer freedom, the freedom that only love and true companionship can provide?

As is often the case with the Christian faith, we are confronted with a paradox. People are image bearers of the living, infinite God, capable of being saints. Simultaneously, we are fragile, finite creatures, with sin making us, as an old hymn goes, “prone to wander” and “leave the God that we love.”

Freedom is, without a doubt, a gift from God, reflecting God’s own freedom, a freedom that led to Creation, Incarnation, and climaxing with Christ freely giving himself in love on the Cross. Yet sin also makes the singular gift of freedom our unique burden.

A gift. A burden. Free to do what we want; free to do what we ought. Free to be who we should; free to be who we should not.

Sirach says to choose “fire” or “water,” but life is never that simple. Often, our freedom overwhelms us. It makes us feel like a raft in a storm. Amidst the storm, drifting further and further from land, we need a boat to come along and throw us a rope. Thankfully, the same God who gave us freedom has never and will never abandon us. And, from the Christian perspective, he did not just send a boat into the storm to guide us through treacherous waters. He sent a man who could command the very storm itself to cease. A man who could walk upon the fiercest of seas like dry land.

Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, one of the most celebrated and well-known texts of the entire Bible, found in the Gospel of Matthew, represents one of the central “ropes” God uses to pull us in from the storms of life. Only spanning three chapters (5-7) of Matthew, you could fill a sizable library of books written solely on the Sermon itself. It shows us how to avoid misusing our freedom.

For two thousand years, Christians and non-Christians alike have found solace, encouragement, and direction in the words of Chris found in this sermon. Of course, for Christians, the Sermon on the Mount is not simply a prophetic message or great ethical teachings (though it is also both of those). Through the confidence of faith, Christians confess it is not simply a man communicating his opinion about the proper use of freedom and how to live good lives. No. It is the God Man speaking. The Incarnated Christ, the Revelation of God breaking into history.

Neither sophisticated philosophical arguments nor a strict list of rules to follow, God reveals in the Sermon on the Mount something altogether more radical. In the Sermon on the Mount, we do not simply read commands but hear an invitation. An invitation to see creation as God sees it. This is not an invitation to a completely new message but the definitive, climatic statement of a vision which began being revealed throughout Hebrew Scripture. In Matthew, God in Christ invites us to do nothing less than transform our moral imaginations.

What does this imagination, this new way of viewing the world, this new way of using our freedom look like? Looking at one passage from the sermon can help us better understand it:

You have heard that it was said to those of ancient times, ‘You shall not murder,’ and ‘whoever murders shall be liable to judgment.’ But I say to you that if you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgment, and if you insult a brother or sister, you will be liable to the council, and if you say, ‘You fool,’ you will be liable to the hell of fire. So when you are offering your gift at the altar, if you remember that your brother or sister has something against you, leave your gift there before the altar and go; first be reconciled to your brother or sister, and then come and offer your gift. Come to terms quickly with your accuser while you are on the way to court with him, or your accuser may hand you over to the judge and the judge to the guard, and you will be thrown into prison.

- Matt. 5:21-25

Christ expands and adds to previous commandments. One should not only not murder their neighbor, but one should avoid anger directed towards their neighbor altogether. You should take steps not only to forgive but to be forgiven. Before you are reconciled with God, you must be reconciled with one another.

The moral imagination displayed in the Sermon of the Mount entreats us to see the world anew. This imagination directs us to use our freedom to live out a vision where compassion, forgiveness, humility, mercy, reconciliation, and care of the most vulnerable are at the forefront of every moment of our lives. These elements of that divine vision are alluded to throughout the entirety of the Sermon on the Mount.

So, freedom is a gift, and the Sermon on the Mount shows how we should use it. But what does this look like in the real world? Where has this moral imagination been put into practice? As a history teacher I naturally turn to the past for examples, to, in the words of Rehniold Neibhur, be emancipated “from the tyranny of the present.” I can think of no one in American history who better demonstrated the moral imagination found in the Sermon of the Mount than Abraham Lincoln.

Historians have long debated Lincoln's personal religious beliefs and continue to do so. We will probably never know for sure what they were. Besides, who can truly know the faith of another? However, Lincoln’s avid reading of scripture and familiarity with the Bible can not be disputed. Regardless of what his faith or lack thereof may have been, in my view, Lincoln still demonstrated, more than anyone else, the proper use of freedom. He embodied, even if unconsciously, the moral imagination Christ preached in Matthew.

Visit the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, and you will see two of Lincoln’s speeches etched on the marble walls: the Gettysburg Address and his Second Inaugural Address. The Gettysburg Address is the better-known of the two. Its masterful cadences and brevity allow it to be easily taught to school children. But I agree with historian Ronald C. White, the author of the definitive book on the subject, Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural, that the second speech listed at the memorial stands not only as Lincoln’s greatest speech but one of the greatest speeches in our history.

American history, James Baldwin once wrote, “is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.” No episode in that history better affirms this observation than the American Civil War. At root, the war was waged over the nation's highest ideals and aspirations, confronting our national inconsistencies and hypocrisies.

It was a terrible refining fire, answering in the blood of hundreds of thousands and in the tears of millions the many questions left unanswered at the Founding, the chief of which being would the nation be “half slave and half free?” Lincoln delivered the Second Inaugural as the war was coming to an end after four long, bloody years.

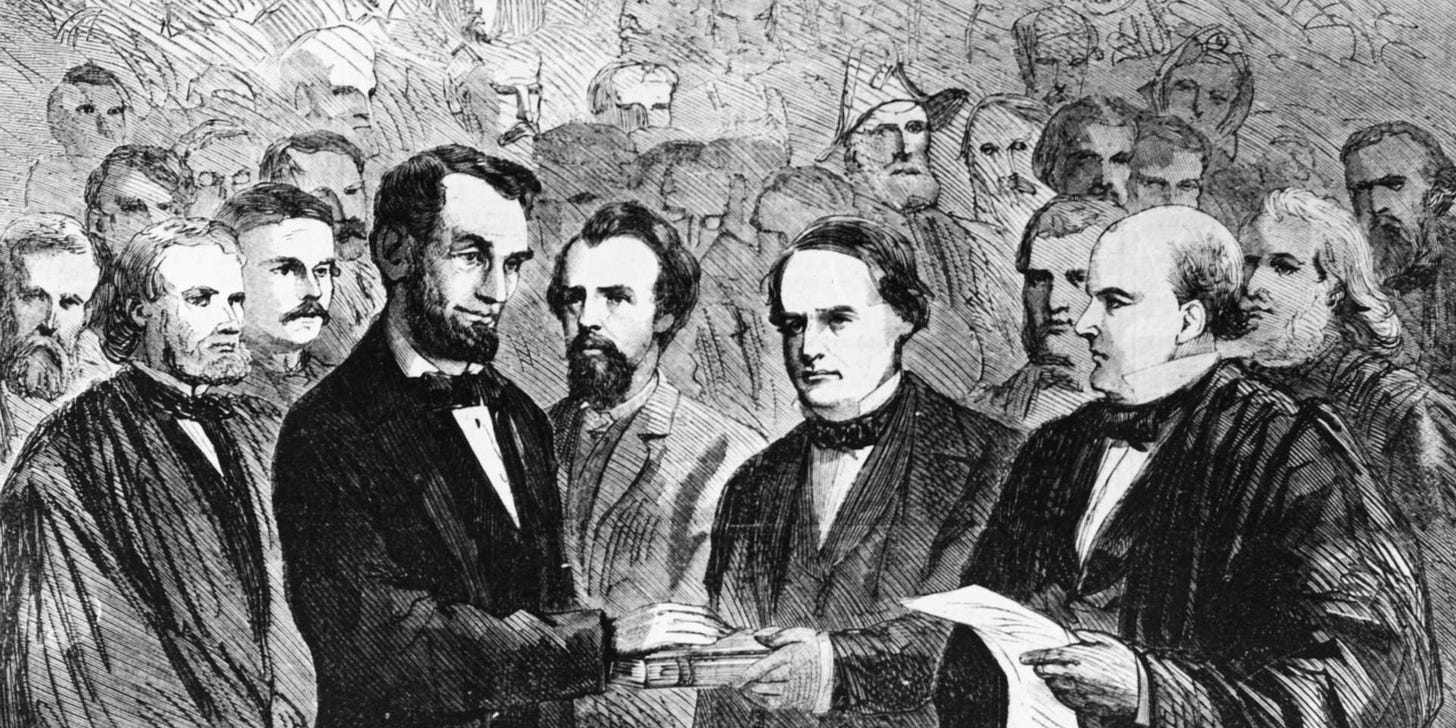

Frederick Douglass was in the large audience, which gathered outside the U.S. Capitol on March 4, 1865 to hear the speech. In his third autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, published in 1881, Douglass reflected about the day and Lincoln’s speech. Douglass wrote that, “The whole proceeding was wonderful, quiet, earnest, and solemn. From the oath as administered by Chief Justice Chase, to the brief but weighty address delivered by Mr. Lincoln, there was a leaden stillness about the crowd.” The speech itself “sounded more like a sermon than like a state paper,” Douglass wrote.

After quoting from the speech at length, Douglass presents a powerful description of his own relationship with it:

“I know not how many times and before how many people I have quoted these solemn words of our martyred President. They struck me at the time, and have seemed to me ever since to contain more vital substance than I have ever seen compressed in a space so narrow.”

-Frederick Douglass

Later that night, Douglass decided to attend a public White House reception celebrating the inauguration, a bold action since it was hitherto unheard of for an African American to attend such an event. Initially denied entry because of his race, Douglass eventually gained entry.

Upon entering the room where Lincoln stood, Douglass recalled the President excitedly exclaiming to the room, “Here comes my friend Douglass,” shook his hand, and asked for his opinion of the speech. Douglass attempted to downplay the value of his views, but Lincoln responded that “there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more.”

Douglass was no doubt surprised at Lincoln’s public reception of him and his words of admiration, considering he was once one of Lincoln’s fiercest critics among abolitionists and the racist attitudes of the era, even among many white anti-slavery advocates. Little wonder he wrote about it with such clarity sixteen years later. Douglass’s terse answer to Lincoln’s question regarding his opinion of the speech was as profound as it was accurate : “Mr. Lincoln, that was a sacred effort.”

Dr. White notes in his book that Lincoln quoted directly from the Bible four times. One verse quoted, “Judge not, that ye be not judged,” (Matt. 7:1, King James Version) came from the Sermon on the Mount itself. In the eighteen inaugural addresses preceding Lincoln’s, only one president, John Quincy Adams, had quoted the Bible in his address, and he had only done so once. A newspaper fittingly called the second inaugural “Lincoln’s Sermon on the Mount.”

This was Lincoln’s moment of triumph. Slavery was abolished, the Union saved and soon to be restored. Lincoln was vindicated. In November 1864, he had been the first president in almost thirty years to be reelected for a second term. Now was a time for bragging. It was a time to lay out the punishments that would be inflicted upon the former Confederacy. But the speech Lincoln delivered was something different altogether.

Lincoln made no boasts. Never denying the South’s culpability, he also noted Northerners and Southerners alike hoped to avoid the war. When confessing his view that the war was, in part, just punishment for the sin of slavery, Lincoln again avoided signaling out the South alone. All Americans were partially guilty. When speaking of God, Lincoln did so with a profound sense of humility. “Fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away,” offered Lincoln, invoking prayers not for victory but peace for all.

In the concluding paragraph of the speech, Lincoln provided a moving call for mercy, forgiveness, and compassion, with a focus on the most vulnerable:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

-Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address

Lincoln was attacked by many in the North, accused not only of being too lenient towards the South but for bluntly stating no American was innocent of the horrible institution that caused the war. “On this memorable occasion, when I clapped my hands in gladness and thanksgiving at their utterance, I saw in the faces of many about me expressions of wildly different emotion,” remembered Douglass. He could not know just how true this observation rang, for John Wilkes Booth was also in attendance that day.

Refusing to brag, blame, or seek revenge, Lincoln spoke with humility, while never downplaying the injustice of slavery nor denying the justice of its abolition, horrible as the price was. “The searing light of Lincoln’s moral judgment,” Dr. White writes, “is refracted through a justice that is evenhanded.” Lincoln’s Second Inaugural embodies the moral imagination at the heart of the Sermon on the Mount. He possessed the immense power of a victorious leader, and had the freedom to lay out any vision he wanted. Lincoln revealed a vision of compassion, justice, and forgiveness, using his freedom to issue a call to care for the most vulnerable and promote a message of reconciliation.

Sirach instructs us that “Before each person are life and death and whichever one chooses will be given (Sirach 15:18).” What a decision. What responsibility. What freedom. Freedom, the gift and burden that threatens to overwhelm. Few will ever face the “fiery trial” which confronted Lincoln, but his example shows us what happens when we embody God’s invitation to see and approach the world through the lenses of the Sermon on the Mount.

Lincoln’s assassination a month and half after the Second Inaugural shows us that even if we use our freedom to follow the way of “life,” the world will often meet us with the way of “death.” This does not surprise Christians, for we follow a crucified Savior. Tragically fitting, Lincoln himself was assassinated on Good Friday and died on Holy Saturday.

Prayerfully, most of us will never face actual martyrdom. But if we allow the Sermon on the Mount to shape our moral imaginations, rest assured, rejection, ridicule, and resentment will inevitably be our lot at times. Yet we have, as a hymn goes, a “blessed assurance,” that through “perfect submission,” we shall experience “perfect delight.” We should never downplay or ignore the horror and suffering of the Cross on Friday, but also let us never forget an empty tomb on Sunday. The Chrisitan story is not one of optimism but one of deep hope, one that recognizes tragedy, but also one, as Rehnold Niebhur said, which takes us “beyond tragedy.”

Let us commit ourselves then to the vision at the heart of the Sermon on the Mount, a vision our nation and the world so desperately needs. A vision providing answers many Republicans and Democrats, Americans and non-Americans, are crying out for. God provided this answer through Jesus Christ because they are all, beyond any superficial identifiers, first and foremost, his beloved children, created and molded in his own image.

This is our story. This is our song. A story of freedom and responsibility. A song of hope and love declaring to all that hear it: “Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy (Matt. 5:7).” God grant us the courage to sing it loudly like President Lincoln did even amidst the maelstrom of war.

Kenly Stewart is a freelance writer researching and writing on a range of topics addressing politics, religion, philosophy, and history. He completed undergraduate studies in history and religion at Campbell University, and received his Master of Divinity from Wake Forest University. A proud public school teacher, he currently teaches high school social studies in North Carolina. @StewartKenly