Tradition and Liberty

Taken together, tradition & liberty represent not the endpoints of two competing ideologies, but one united ideology—the logical endpoint of a Burkean, Smithian, Hayekian, Humian constrained worldview

Shorn of any commitment to free markets and limited government, conservatism can become little more than fondness for the past wedded to moral orthodoxy and cantankerousness towards change. Shorn of any commitment to incrementalism, virtue, republicanism, constitutionalism, or religion, the pursuit of liberty can devolve into moral relativism.

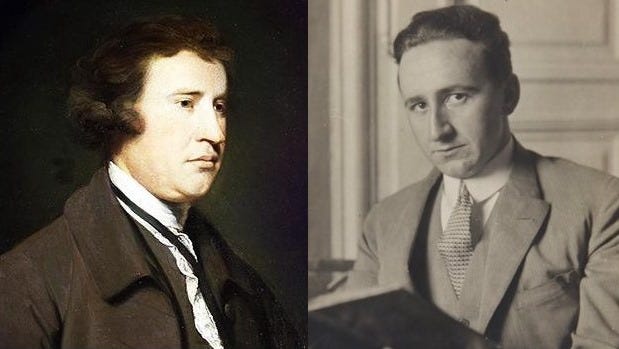

Despite all the arguments to the contrary, tradition and liberty are natural allies. Burke wrote about emergent order in tradition and politics and the structure of society—the gradual evolution over time, the systemic knowledge of individuals acting independently, the accumulated wisdom of generations that survive the competitive and dynamic tests of time. Hayek wrote about emergent order in the economic, legal, and scientific realms—the systemic wisdom of the market, the living processes that create prosperity and allow for autoregulation, capitalism’s ability to respond to shocks, etc.

Each man admired common law. Despite Hayek’s insistence that he wasn’t a conservative, there was a temperamental conservatism to his free market principles. Despite his reputation as a defender of hierarchies, Burke supported markets and free trade and believed in social and economic change, so long as it came slowly through evolved and bottom-up processes, rather than rapidly through top-down imposition.

Indeed, there is no contradiction between Burke’s traditionalism and his support for markets, or between Hayek’s libertarianism and his love of accumulated wisdom which evolves over time. Both a commitment to tradition, and a commitment to liberty, spring from a constrained worldview.

Conservatism Without Liberty

Whenever conservatives attempt to do away with commitment to free enterprise, they run into a problem. The left has its economic philosophy. If the right jettisons capitalism, it does not. We can’t go back to mercantilism, and mercantilism never really made sense as an economic philosophy anyway—something which has been understood by economists going back to Smith and Ricardo.

Without a competing economic philosophy, right-wingers begin implicitly or explicitly embracing socialism or progressivism, echoing communism or radicalism, or rehashing leftist critiques of the free market, whether or not they understand themselves to be doing so or not.

And much as some on the right try to explain that you can have a right-wing socialism, you can’t. What happens instead is that those who used to call themselves conservatives move gradually further and further to the left until they have jettisoned their conservatism and embraced progressivism. They set out to move socialism to the right, thinking that they could change socialism. Instead, socialism changes them.

We can already see this among nationalists and populists, some of whom began as anti-capitalists and others who have come to that position. Over time, they have accepted more and more of the left’s premises (about the market, about the state, about liberalism, about society) as true.

There were some who started their journey as conservatives who just sort of liked Donald Trump, and over time they came to reject more and more of what they previously believed until they had accepted nearly all of the premises of their ideological opponents (and it will only be a matter of time before they accept those opponents’ positions).

That road leads only to the death of the conservative movement, which was exactly what many conservatives said in 2015.

Individualism Without Conservatism

Some individualists like to pretend that they aren’t on either the right or the left. Many take great pains to distance themselves from the right especially.

Some even like to be anti-patriotic, having bought the leftist claim that fascism is a right-wing ideology which stems from patriotism. But an ideology of maximal liberty which rejects patriotism quickly devolves into ingratitude (patriotism being fundamentally about gratitude for one’s home). And classical liberals in America should be especially grateful.

We may have slipped a little in our commitment to the free market, but America remains the most individualistic country in the world (we have a First and Second Amendment, for instance), and without America, the world would very quickly reassemble itself into a far more tyrannical hellscape than it is today.

Some individualists are too quick to abandon institutions and traditions. They are in danger of losing sight of Hayek’s Burkean argument about the evolution of emergent order. Continuity with the past, rather than wholesale rejection of it, is central to the free market and to free society.

And institutions should rightly be seen as complementary to individualism. Together, individuals and the associations they build, from civil society—and it is this civil society that is most threatened by the encroaching state. When Tocqueville contrasted American self-government with his home country of France, he noted that his countrymen cried out for the state to step in to solve every problem. In America, individuals came together and formed organizations to solve those same problems themselves. Lovers of freedom should reject the false claims that small governments lead to atomization. They should forthrightly make the case that the opposite is true.

When individualists emphasize socially liberal policies, they sound like they are making common cause with progressives. But progressives will never join the project of shrinking the size of the government. This is antithetical to progressivism, which requires a strong state. Progressives are cousins to socialists—hostile to markets, individualism, property rights, and decentralization.

An individualism that lacks a temperamental conservatism presents only one-half of the case for individual liberty—a case shorn of responsibility. It is a case that argues only for letting Americans freely do drugs, without any room for explaining why they should choose not to. It is a case that avoids offering a strong alternative to the current zeitgeist in which it is commonly believed that there is no way to make people do the right thing without forcing them, rather than offering arguments based on the idea of individual moral responsibility.

A true alternative to the current zeitgeist argues that the weakest solution to family breakdown, sexual licentiousness, and atomization is to say that the government should “do something.” It argues that rebuilding the family can only begin in the home, that chastity can only begin with the individual, that loneliness can only be combatted by comforting lonely individuals. It argues that conservative ends and libertarian means can travel together because libertarian ends and conservative means can travel together.

Partners in Freedom and Virtue

Ultimately though, the reason that traditionalists and classical liberals need one another is that the most profound argument in favor of liberty is the moral one. The most inspirational case for capitalism is the moral case.

There is an argument in some circles that capitalism is, at best, amoral (and, at worst, immoral), and that freedom isn’t good for anything because freedom is soulless and lacks the moral vision that cohesion and community can provide. Thus, at best, virtue and freedom are shaky partners, and, at worst, they are at odds.

Not all religious people believe in free will, but among those who do, one of the most powerful religious arguments for free will is that moral decisions are only moral if they are chosen freely. Virtue is only virtuous if it is a choice, which implies that there must be an alternative choice to do evil, rather than good. Free will, in that telling, is a prerequisite for doing good.

Some interpret this as a claim that freedom is a secondary good, good insofar as it allows people to have virtue. And some go farther, saying that if freedom is good only as a means towards the end of getting people to choose virtue, then it fails. People choose what is bad. Therefore, freedom must be rejected and virtue-by-any-means-necessary must be embraced instead. But this is a mistake. The actual implication of the case for free will is that without free will, virtue is impossible. Virtue, without freedom, isn’t virtue.

But an even stronger argument for the political link between freedom and virtue is that freedom isn’t good merely as a means to an end. Freedom isn’t good merely because it allows people to do what is right. Freedom is right.

Some individualists err in presenting liberty as an empty vase into which each individual can pour his or her vision of the best life. Conservatives who reject this relativism are correct to argue that not all visions of what is best for human life are created equal. But they err in thinking that the best life is still the best life when it is forced upon people. It is not. It ceases to be the best life.

Why? Because the best human life includes freedom. It is good and right and just for human beings to be free to choose, free to think, free to profit from their labor and their ideas, free to trade, free to barter, free to enter into partnerships and contracts and associations, free to use that which belongs to them (i.e., their property) in whatever way they deem fit, free to exchange value for value, free to compete, free to pursue the greatest human achievements that they can, free in their private lives and in their public ones (in the institutions and associations where they come together of their own accord to do things and to be with one another in community), free to rise by their own merit, and free to give up some of their freedom so long as they part with it willingly and in full understanding of the consequences (i.e., freedom to join a church which demands they wear certain clothing and refrain from eating certain foods, freedom to enter into a marriage where they will take on the burden of raising children, freedom to take a vow of poverty and forego their ability to earn a higher wage, etc.).

Much better writers than me have made the moral case for freedom, but it isn’t one that we hear commonly today. Which is sad. Too many people have given up on free enterprise because they believe its only purpose is to make them rich (whereas socialism claims to offer people a moral world). But prosperity isn’t the only purpose of free enterprise. It isn’t the only reason why free enterprise is the best economic system. Free enterprise is good because it allows human beings to profit from their own labor and ingenuity. Free enterprise is good because it allows individuals to thrive. Socialism, mercantilism, and every other economic system put forward are zero-sum. Free market capitalism is positive sum. It isn’t better for the rich. It is better for everyone.

When conservatives give up on the market, they give up on the idea that a freer world is a better world. And they give up on the idea of a better world. When right-wingers give up on virtue and embrace moral relativism, they will lose every argument because the left can make the moral case for relativism much better than right-wingers can.

Taken together, tradition and liberty represent not the endpoints of two competing ideologies, but one united ideology—the logical endpoint of a Burkean, Smithian, Hayekian, Humian constrained worldview. We of the constrained worldview may disagree amongst ourselves about many things, just as our ideological opponents on the left do. But we should make no mistake about the fact that we are on the same side, for if we make that mistake, we lose sight of part of what is best about our vision of the world (and if we do that, we move closer towards accepting the other side’s vision).

There are still fusionists today making these arguments. But sadly, many today have forgotten that fusionism wasn’t merely a compromise between competing ideological traditions faced with the threat of communism. It was, and is, an enduring vision of one ideology.

Ben Connelly is a writer, long-distance runner, former engineer, and author of “Grit: A Practical Guide to Developing Physical and Mental Toughness.” He publishes short stories and essays at Hardihood Books. @benconnelly6712

"Virtue, without freedom, isn’t virtue." Very well said.