What Is the Best AR-15 zero?

Adding my own two cents to the never-ending debate about the best zeroing distance for an AR-15 shooting 5.56/.223.

There is a much-debated and never quite settled issue in the world of AR-15s: what is the best zeroing distance. Often, it’s a debate of tradeoffs. An AR-15 is capable of extreme accuracy at short, medium, and long distances. But the ballistic realities of a 5.56/.223 round makes it so that you cannot truly have extreme accuracy at all three, no matter the zeroing distance chosen. So, what is the best tradeoff? Often, that’s a matter of opinion and experience. In this article, I will offer both my opinion and experience.

First, let’s qualify that while 5.56/.223 can be fired accurately at considerable distances, many studies have concluded that the terminal effectiveness of the round is 300 yards. So, for combat application purposes, the best zero relates to total deviation in the flight path of the round from point-blank range out to 300 yards.

From this standpoint, we can dispense with point-blank zeroing distances, such as 10 yards. Such close zeroing distances do not change the mechanical offset, meaning a 2-inch manual offset will still be needed for point-blank aiming, and such zeroing distances lead to a dramatic loss of range almost immediately (at least 2 inches at 25 yards, more than 5 inches at 50 yards, and almost a foot at 100 yards). Point-blank zeroing distances essentially make point-of-aim useless through the entire path of the bullet while only marginally increasing point-blank and short-range accuracy.

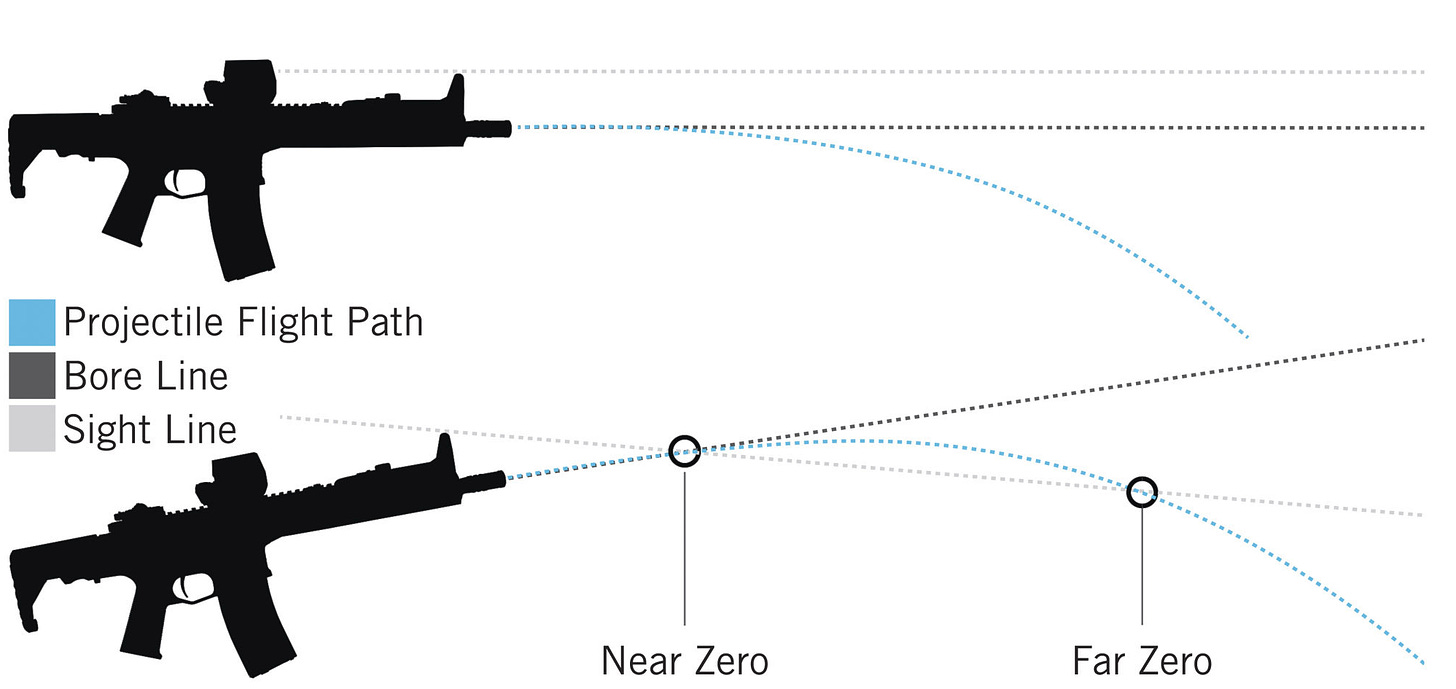

Next, we can dispense with any zeroing distances beyond 100 yards. The most effective zeroing distances for 5.56/.223 are ones that create two points in the flight path of the round, under 300 yards, that allow for point-of-aim, point-of-impact shots. Zeroing distances beyond 100 yards are effectively apex zeros, which means the only time the bullet crosses point-of-aim is at the apex of its flight.

This generally leaves us with four popular zeroing distances: 25 yards, 36 yards, 50 yards, and 100 yards.

The 25-yard Zero

At first glance, the classic 25-yard zero is the best zeroing distance across the entire length of terminal effectiveness. At most, it deviates 3-4 inches from point-of-aim and should impact at 300 yards with less than 2 inches of drop. While sacrificing some accuracy in the medium ranges (+3 inches in the 100-200 yard region), a good center-mass shot should impact the kill zone using point-of-aim across the entire length of terminal effectiveness. This is probably why the 25-yard zero has been so consistently used in the military. Point and shoot, nothing fancy, leave the tick-hair shaving to the snipers and designated marksman.

But there are some questions we should pose about the 25-yard zero. Is what we are getting in return for sacrificing medium-range accuracy worth the tradeoff? Arguably, the 25-yard zero does not give us an increased enough accuracy at short range to justify a deviation as high as 4 inches at 150 yards. Yes, with a 25-yard zero, we can still engage targets easily using point-of-aim at 300 yards. However, point-of-aim is probably more valuable at medium range, and manual offset is easier to perform with less immediate stress (i.e., more distance from someone who’s shooting back at you). To be frank, I’m sure Taliban fighters engaging American forces at medium distances have had a lot of lead fly over their heads.

The 100-yard Zero

So, let’s go to the other end of the popular zeroing distances: 100 yards. The 100-yard zero essentially focuses in on the common distances of engagement and is especially popular with carbines, SBRs, and pistol-builds. The 100-yard zero enables a slow-rising flight path that begins at mechanical offset (2 inches at point-blank range) and rises to point-of-aim at 100 yards. This allows for a point of impact with a deviation of under an inch in the 25-150 yard area. This means that not only is point-of-aim useful within all common distances of engagement, but high percentage shots can easily be undertaken in those distances using point-of-aim (A high percentage shot would be a head shot at medium ranges and a cranial cavity shot at short ranges). For example, defeating body armor would require manual offset at medium ranges with a 25-yard zero, whereas a 100-yard zero allows point-of-aim.

Despite its clear advantages at short and medium ranges, the 100-yard zero makes heavy sacrifices beyond 150 yards. This is because the 100-yard zero is effectively an apex shot. The bullet only reaches point of aim at the apex of its flight. After it passes 100 yards, it begins to drop again. At 200 yards, it already drops over 2 inches, and by 250 yards, the drop is up to half a foot. At the 300-yard mark, the deviation falls to ten inches. You would be at a clear disadvantage against weapons sighted in for long-range accuracy in a combat situation. You’d be good for home defense on the civilian side, but you can forget about hitting a running coyote or other varmint past 150 yards.

Frankly, the 100-yard zero should probably have never become as popular as it has. Using an apex zero dramatically limits the sweet spot area of a zero by creating only a single distance where point-of-aim is point-of-impact. A quick look at the 50-yard zero demonstrates that it does what the 100-yard zero purports to do much better because it affords two point-of-aim, point-of-impact distances instead of only one.

The 50-yard Zero

The 50-yard zero increases the point-of-aim sweet spot of the 100-yard zero by 50 yards (25-200) while saving about 2 inches of drop at 250 yards and 1 inch of drop at 300 yards. The 25-100 yard area deviations are only marginally different and are considerably improved at 150 yards. On paper, there is really no argument for the 100-yard zero over the 50-yard zero. Simply put, the 50-yard zero does what the 100-yard zero does better. All striking distances with a 50-yard zero between 25 and 100 yards are within .5-inch of the 100-zero, the 150-yard striking distance is .5-inch better, and the bullet returns to zero (point-of-aim, point-of-impact) at around 175 yards with a 50-yard zero while it has already fallen between 1 to 2 inches with a 100-yard zero.

But the same case that makes the 50-yard zero better than the 100-yard zero is also the case against it. Is it truly the goldilocks zeroing distance? If, on paper, it looks like a more finely tuned 100-yard zero, how is that supposed to be splitting the difference between the 25-yard zero and the 100-yard zero? If the 300-yard impact of a 25-yard zero is less than 2 inches deviation from point of aim, and the 50-yard zero and 100-yard zero are 9 and 10 inches respectively, then clearly we are making the same sacrifices using a 50-zero as we are using a 100-zero, if not a more modestly mitigated sacrifice.

The 36-yard Zero

This is why so many have begun using the 36-yard zero. Arguably, if we’re looking for a true compromise between the 25-yard zero and the 100-yard zero, the 36-yard zero may be just what we’re looking for. The 36-yard zero creates a +/- 1.5-inch sweet spot from 10-200 yards, drops 2 inches at 250 yards, and drops 6 inches at 300 yards. This means, point-of-aim can be used for center-mass shots out to 250 yards, and 300 yards would require only a slight manual offset. Further, point of aim can be used for high percentage shots out to 200 yards. The 36-yard zero effectively mitigates the sacrifices of both the 25-yard zero and 100-yard zero by tightening up both the medium and long distances, essentially spreading deviation across the entire length of travel.

Is There a “Best” Zero?

So, what’s the best AR-15 zero? Well, it depends on what you want. If you want a point-and-shoot AR-15 that hits center mass across the entire terminal effective distance, the traditional 25-yard zero is what you want. If you don’t ever plan on using your weapon beyond 150 yards, the 50-yard zero will give you dead-on accuracy within that range. If you want a gun that grants respectably high accuracy at short and medium ranges while still capable of long-range application, the 36-yard zero is your sweet spot.

Optics can also make a big difference in consideration. A scope with ballistic markings, for example, works best with an apex zeroing distance in contrast to what might work best with open sights or reflex sights. My set-up on my personal AR-15, for example, uses two zeroing distances. I have a 1-4 AR scope with ballistic markings made for a 100-yard zero. Each mark represents another 100 yards in distance. With this consistent ballistic representation, I have a rifle capable of hitting center-mass equivalent targets hundreds of yards beyond terminal effective distance. But I also have canted open sights mounted on my rifle, which I chose to zero-in at 36-yards so that I can take advantage of the longest possible sweet spot with a point-and-shoot application conducive to when these sights would have to be used.

And, finally, it should be remembered that different guns and different types of ammunition can have dramatically different ballistics. At the end of the day, the kinds of data we can get from ballistics calculators always have to be confirmed on the range. If you have an AR-15 and want to know which zeroing distance works best for you and your rifle, go to the range, try out different things, and find out what you and your rifle are capable of before deciding what it is that you like.

You should use meters, not yards. The military does.