The establishment of Reed’s Rules was a defining moment in our history. It was another step away from the system of separated powers and checks and balances designed by our founders and toward the majority rule they had tried to protect against. The rules concentrated power into the speaker and the majority party. The rules shaped the House from a deliberative body meant to represent the people, which was inefficient during times of peace, into an efficient machine for party rule. Republicans and Democrats both won, and the American people lost.

Majority power describes the role of governing bodies via simple majority rather than the concurrent majority often required in our constitutional system. Following the Civil War, majority power was transferred from the South to the North but maintained divisions. Passions were tempered nationally for a brief moment during reconstruction, but tempers flared again during the election of 1876. The divide spread past the regional differences of slavery and into the party differences of the nation.

The thread of majority power began in our founding era with Alexander Hamilton and the Federalists. Then, it was woven into the Antebellum era with Andrew Jackson and the Democrats and then woven again into the new Republican Party with Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War and Reconstruction. The Federalists had a fundamental belief that people were not fit to govern themselves and, therefore, needed a ruling class. The Antebellum Democrats wanted to preserve slavery, and they saw no other way to accomplish this goal other than majority power. The new Republicans of the Civil War wanted to abolish slavery. They were forced to unite and meet power with more power.

By 1889, the partisan divide found the House often mired in deadlock, with minority parties using obstructive tactics to halt progress. It was a time of filibusters and endless debates, where a simple "call to quorum" could stall proceedings indefinitely.

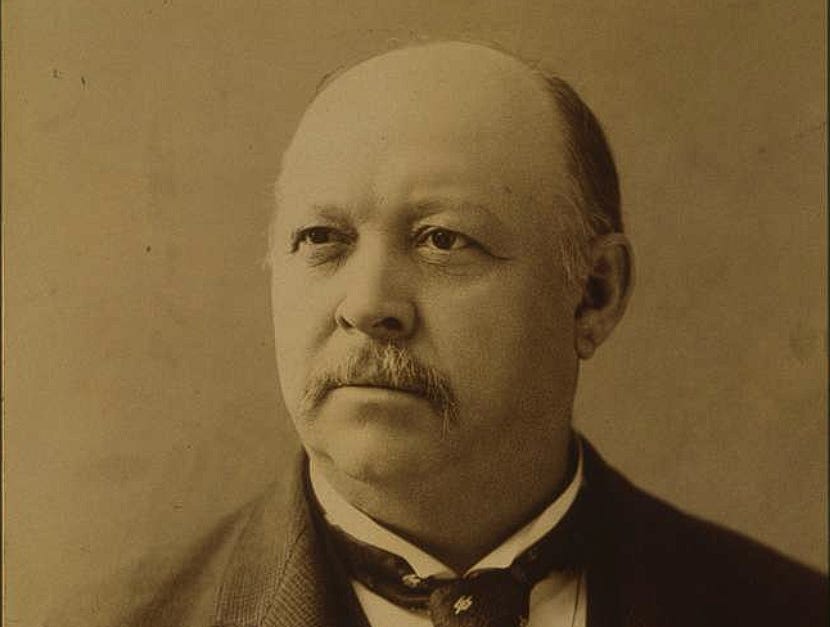

Thomas Brackett Reed, a Republican from Maine, was a stubby bald figure with a sharp wit and a mind to match, and he was determined to streamline the house by instituting majority power. Reed was frustrated by the use of the Disappearing Quorum. The minority had the ability to block legislation by preventing a quorum—the minimum number of members who must be present for the House to conduct its business—through the simple act of not answering roll calls, even though they were physically present in the chamber.

Reed defeated the future president and Ohio Representative William McKinley for the Speaker of the House in the Fifty-First Congress. Typically, the rules committee would report rules for the House to adopt and operate within, but for the first month of the speakership, Reed chose not to adopt formal rules for the House. During this time, Reed didn’t even bother to call a meeting between himself and the committee, made up of two Democrats, John Carlisle and Samuel Randell, and two Republicans, William McKinley and Joseph Cannon.

When members questioned the lack of formal rules, Reed instructed them the House would operate under general parliamentary law. When issues arose that were ambiguous in nature, Reed would be empowered to decide what was general parliamentary law.

During this unruly time, the House did not take much action other than the routine until January 29th, 1890. Reed decided to take up some of the election cases pending in the House. In this time of partisan warfare, the House was charged by the Constitution to resolve election disputes. Often, the party in power would use this as an opportunity to unseat an opposing party member and seat one of their own.

Earlier in the day, a bill was passed with 187 yeas, 98 nays, and 43 not voting. The contested election case of Smith v. Jackson was presented, and the roll was called for a quorum. There were 162 yeas, 3 nays, and 163 not voting. Just like that, the quorum had disappeared.

What happened next shocked both Republicans and Democrats. Reed instructed the Clerk to record the names of those present but not responding, and a quorum was declared. Pandemonium broke out. Reed, unfazed by the uproar, famously retorted, “The Chair is making a statement of the fact that the gentleman from Kentucky is present. Does he deny it?” Laughter and applause erupted from the Republican side.

The bold move was a pivotal moment that led to a series of procedural changes known collectively as "Reed's Rules." These rules expanded the Speaker's powers and allowed the count of non-responding members to achieve a quorum. They also limited the possibilities for obstruction by reducing the number of motions that could be filibustered and by allowing the Speaker to close the debate and move to a vote when it was clear that further discussion would not change the outcome.

Reed's Rules were met with vehement opposition. Democrats fumed, and Republicans were concerned. Democrat Charles Crisp from Georgia defended the minority’s power of the disappearing quorum by reading the words of James Garfield—the former Republican House member and President who was assassinated by a disgruntled office seeker in 1881. Garfield denounced a similar rule presented by Randolph Tucker of Virginia in 1880 as a partisan rule. Republican leaders William McKinley and Joseph Cannon took the floor to defend the rule, but it was clear by their speech they were unprepared. The battle continued to rage, but the Republicans united, and with their power and majority, the Democrats could not stop it. Thus, the Fifty-First Congress eventually adopted Reed’s Rules.

With the help of Reed’s Rules, the Fifty-First Congress was productive, passing major legislation like the Sherman Antitrust Act, Navy Act of 1890, Dependent and Disability Pension Act McKinley Tariff, and Forest Reserve Act of 1891. They increased spending from $820,000,000 to $1,009,270,471.

After the 1892 elections, Republicans lost control of the House, and Democrats did not adopt Reed’s Rules for the Fifty-Second Congress. Reed found himself in the minority and used the power of the disappearing quorum to frustrate and obfuscate the Democrats. However, little by little, Democrats began instituting their own version of majority rule and adopted the lynchpin of Reed’s Rules. By the time Reed and Republicans were back in the majority, Reed’s rules had been upheld by the Supreme Court and institutionalized by the Democrats.

Reed used his deep knowledge of parliamentary law, deception, and force to establish Reed’s Rules. He kept everyone, including his rules committee, in the dark about the new rules. He unveiled them before a partisan case that Republicans wanted to win, backing them into a corner of support. Then, he used the power of the Republican party to bulldoze them into submission.

Thomas Brackett Reed is an interesting figure. He was a confident man with a sharp tongue. He was an avid reader with a thirst for knowledge—although he could be admittedly lazy and self-indulgent. Reed’s actions came from deep thought and planning. Majority power was his mark, and he was determined to make it. He may have never been President, but he had the temperament and ambition of one.

After reconstruction, the thread of majority power was sewn into the Gilded Age during the Compromise of 1877 and the subsequent investigation of voter fraud with the Potter committee. Reed and the Gilded Age Republicans had similar governing beliefs as Hamilton and the Federalists of our founding era. They believed in a bigger, stronger federal government. They believe those who know best should govern, and everyone else should just watch. They didn’t really believe in governing, they believed in ruling.

Majority power is an efficient tool both for and against tyranny, which is exactly why our founders created a system to protect against majority power. Reed’s support for majority power stands opposite the two greatest political theorists in American history, James Madison and John C. Calhoun. Madison and Calhoun saw majority power as tyranny. Instead, they supported constitutional or concurrent majorities.

A concurrent majority is when, for certain decisions, a majority vote is not sufficient. Instead, there must be agreement among separate, overlapping majorities within the political body. Concurrent majorities give people more power because parties must reach outside their tent to pass legislation, bringing more voices into the process. Concurrent majorities allow citizens to be a “government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

Majority power is ruling. Majority power in the wrong hands is tyranny. The reason our founders didn’t want Majority power is because, over time, power changes hands, and we never know who’s going to be in power next. The Concurrent majority is a check against the “tyranny of the majority.”

“The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.”

–James Madison, Federalist No. 47

Reed’s rules and majority power have shaped our current political discourse. Parties openly focus on combining the layers of our separated powers of the House, Senate, and Executive into one-party control. We are told it's to protect us from the other guy. When in office, parties rule with executive action and thin majorities, all in the name of the people. But it has nothing to do with people. It has everything to do with party power.

Do our rulers even know they are ruling us?

Jeff Mayhugh is the co-founder of the Madisonian Republicans and a former Congressional Candidate for VA10. @Jmayhugh28

Today, I learned about an important figure in American history I never heard of before- T.B. Reed should be better known.

Very interesting!