Will We Teach the Children About the Promised Land?

The curriculum debate is about much more than CRT, it's about whether or not we will continue to teach our children about Dr. King's dream of reconciliation and common brotherhood.

The Civil Rights Movement, as it was led by Dr. King, was both a charismatic Christian revival and an American renewal.

Dr. King argued for equal rights before the law for African Americans using the legacy and imagery of the founders and the framers. Within America’s core ideals, Dr. King found a promissory note that he asserted, defiantly, had gone unfulfilled. Inasmuch as Dr. King sought to transform America, it was only to the extent that it lived up to its creed of liberty and justice for all. In this sense, the Civil Rights Movement was not a revolutionary departure from the American experiment but was the long-awaited, and far too long in coming, apotheosis of the journey begun at America’s founding.

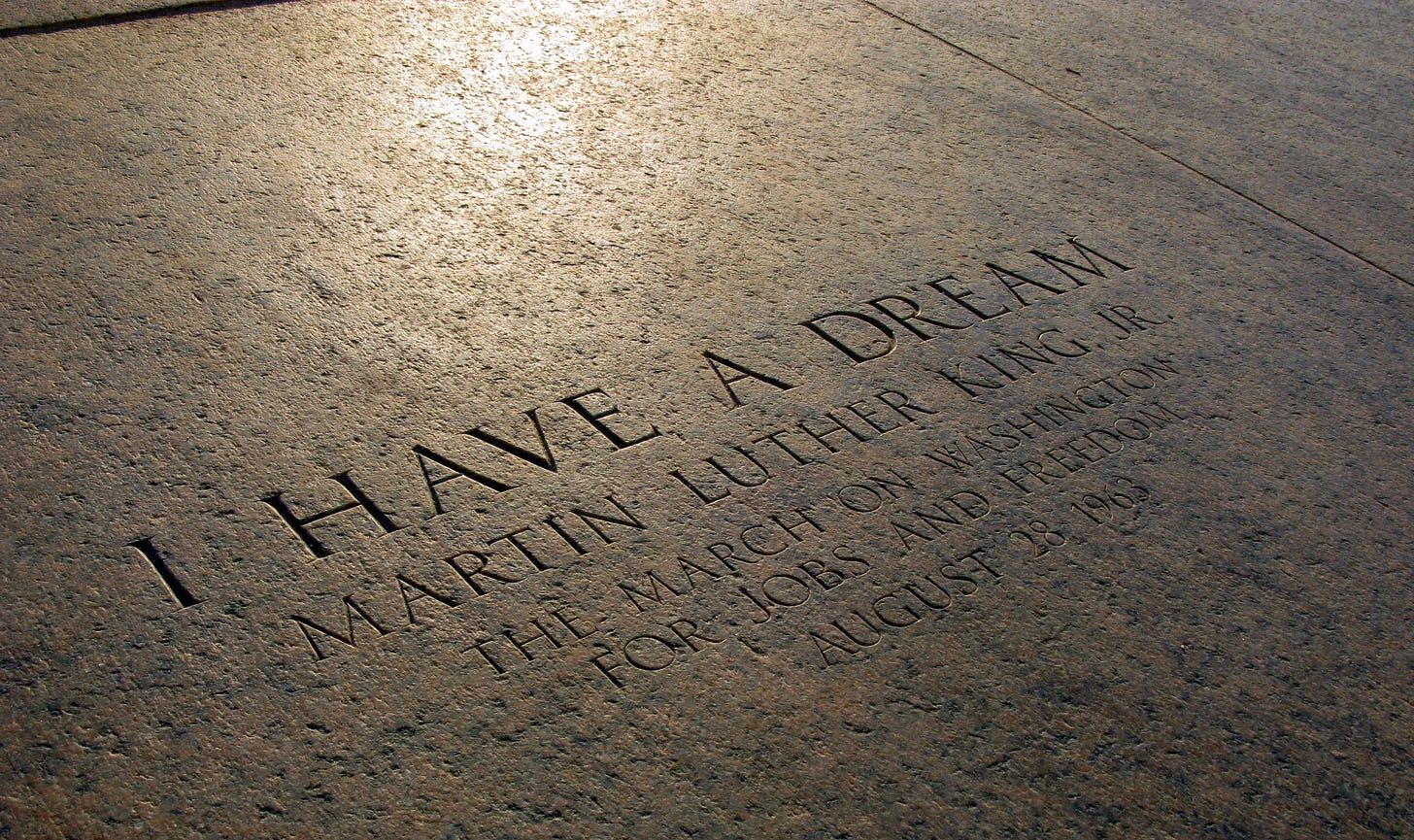

This imagery is at its most potent when, on August 28, 1963, Dr. King stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, in the “symbolic shadow” of a “great American” whose “momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves.” Dr. King spoke of the “magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence” and made a case to his fellow countrymen that despite the promises held within America’s creeds, African Americans had still been denied their “unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

At that historical moment, Dr. King spoke of a dream, a dream he believed could “lift our nation from the quick sands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.” He warned that this dream could not be realized if the passions of racial justice “lead us to a distrust of all white people” and he asserted his firm belief that “their destiny is tied up with our destiny” and that “their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.”

Dr. King’s dream was clear and beautiful. He offered a vision to the country of a time where “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood” and of a nation where no one would “be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Dr. King put his faith in achieving a future where “one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.” He saw in his vision, in his dream, the possibility of a time when “all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning: My country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrims' pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.”

Five years after offering this vision to the country, after sharing his dream, Dr. King gave one last speech before his life was taken and before our country was robbed of one of its greatest citizens. As he spoke this final time of his dream, he said, “I don't know what will happen....But it really doesn't matter with me now, because I've been to the mountaintop....And I've looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

It’s impossible to know what Dr. King would think of where we’ve come as a country since he offered us a glimpse of that which he saw so clearly. At best we can say we have succeeded in part and failed in part.

We have had an African American President. Many of the great athletes and talented artists and performers in cinema, music, and popular culture are African Americans who are celebrated by all races and creeds. In America, there are African American CEOs, military leaders, political thinkers, and the most esteemed of educators who have risen to the pinnacle of success and influence.

And yet, a disproportionate segment of the African American community remains stuck in generational poverty. Our jails and our prisons are disproportionately filled with young African American men. The nuclear family in the African American community faces disproportionate dissolution and decay. African American children disproportionately face life without one, or both, of their parents, they disproportionately end up in foster care, and they disproportionately fail to graduate high school.

Most heart-breaking of all is that the combined result of all these factors has led to a terribly disproportionate level of crime in African American communities, tragically increasing negative and confrontational interactions between African Americans and law enforcement.

We continue to catch glimpses of the promised land that Dr. King saw. But they remain glimpses and it’s often difficult to stay focused on the dream when we are far too often reminded that we still have work to do before we can arrive at the mountaintop.

But one of my towering concerns and my greatest worries, is that there are some whose efforts, whether they intend it or not, would render the promised land a myth and relegate the dream to an anecdote from history.

Today, there are certain doctrines, theories, and alternate projects in understanding history that do not seek to look at the American story, the American experiment, the American system, or even at the progress gained through the efforts of those like Dr. King through the lens of hope and reconciliation. Rather than seeking to forge a nation that lives up to its creeds, the very worth of those creeds has been brought into question.

These ideas and projects go under various names and have different justifications for their tenets and approaches. We can talk about intersectionality, conflict theory, critical race theory, or such things as the 1619 project, but ultimately, we’re talking about theorists and historians who are offering alternate ways to look at history, to look at society, and to look at the very system itself in order to offer a different perspective and challenge the status quo.

Now, as an avowed contrarian myself, I do not feel threatened by new and different perspectives. I love and embrace a free marketplace of ideas and I think that our higher institutions of learning and the academic community are best served by believing in academic freedom and in providing space in the public square for debate and reconsideration of even our most assumed values from all corners of the political compass.

As Thomas Jefferson said, “Fix reason firmly in her seat, and call to her tribunal every fact, every opinion. Question with boldness even the existence of a god; because, if there be one, he must more approve the homage of reason, than that of blindfolded fear.”

And yet, I feel this open-minded quest for knowledge and the provision of space for debate and rediscovery must come with a word of caution. Not everything that is good, and right, and excellent to consider in the realms of higher learning and in the circles of the academic elite or in legal scholarship is proper or healthy to present as a settled issue to the developing minds of those in elementary and secondary schools.

I’ll be as specific and blunt as I can be. I am in no way threatened when in the course of rigorous and academic pursuit of higher knowledge in the halls of college academia I am confronted by those who have embraced views contrary to my own on the efficacies of the American system, on the wisdom of the founders and the framers, or even on whether reconciliation and the dream as presented by Dr. King is possible. I wouldn’t believe what I believe if I was afraid of having my beliefs confronted and challenged. However, I am greatly concerned and deeply troubled when the proponents of these contrary and alternate views seek to skip the rigorous academic debates which all sociological and political theories must endure before broad acceptance and take these ideas to the places where the minds of our impressionable youth are molded and crafted.

I am deeply concerned and troubled by a growing possibility that my little children will not be judged based on the content of their character but on the color of their skin, that their impressionable minds will be taught by their teachers to think of themselves as defined by their race and to identify as little white children, when I have endeavored to teach them to think of themselves as citizens of a community, of a nation, and of a worldwide family called the human race.

Today, as we celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I honestly wonder whether my efforts to teach my children of Dr. King’s dream, to pass on the vision of a promised land I believe we can find and enter into together, and to hand off the torch of America’s unfinished revolution began by the originators of our creeds might become thwarted. Our nation, and specifically our educational system, is becoming swarmed by those who think it’s time to teach America’s children that such endeavors are hopelessly tainted and that unless they are taught to surrender a belief that we should be “a nation of laws and not men” and confess their privilege and embrace and take upon their shoulders the burden of generational guilt and sin, that unless they do these things they will be considered the oppressors, the problem, and the enemy.

In such a future, will the children know there was a promised land?

Justin Stapley received his Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Utah Valley University, with emphases in political philosophy, public law, American history, and constitutional studies. He is the Founding and Executive Director of The Freemen Foundation, the Editor in Chief of the Freemen News-Letter, and is also a Federalism Policy Fellow at UVU’s Center for Constitutional Studies. @JustinWStapley