Taylor Swift and the Purpose of Music

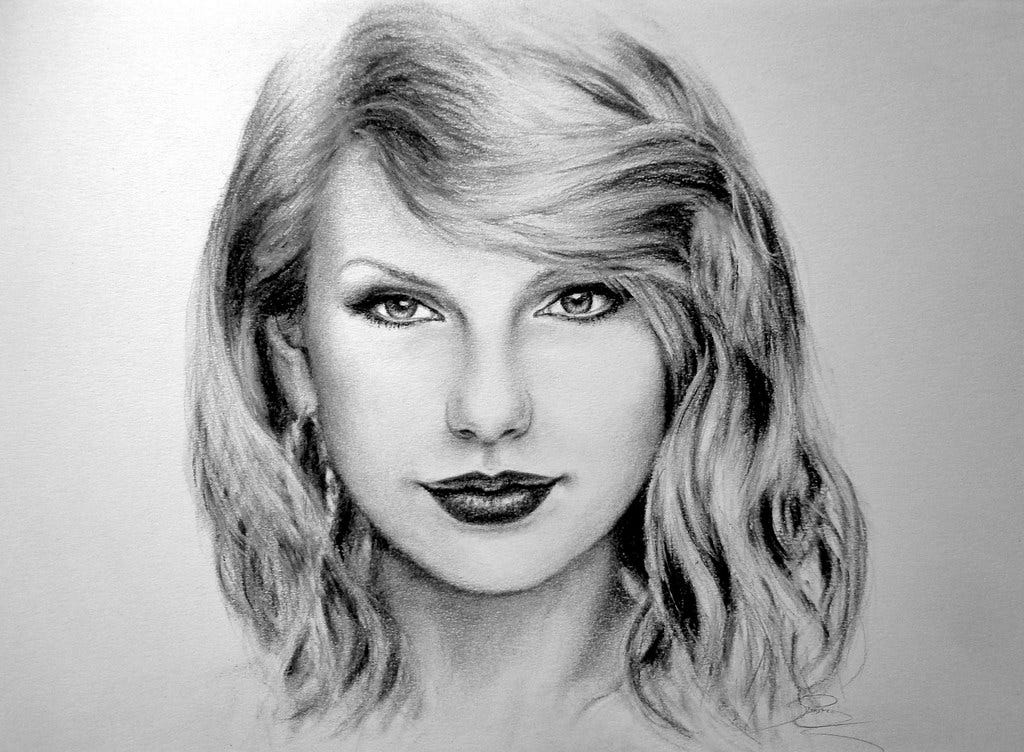

Taylor Swift is to be congratulated for her dominance as a highly successful entertainer, but her lack of artistic qualities reflects the lack of depth in contemporary music.

Since the advent of the phonograph and the radio, but certainly over the course of the last seventy years, generations beginning with the youth of the time, flush as their pockets were with spending cash, were deferred to and crowned society’s taste setters. The machinery that churns out celebrities was refined to a science. We’ve both asked too much of music and grown ignorant of its real value.

Music was developed as part of our quest for beauty. Plato said that the acknowledgment of beauty in a physical object or scene was essentially a recognition of this a priori condition of the way the universe is constructed.

In The Republic, his conversants, Socrates and Glaucon, feel that musical harmony is such an important matter that they discuss what kinds of scales ought, and ought not, to be taught to the young people of the ideal State they’re constructing. (I personally find their conclusion that kids ought to be kept away from the Ionian (major, do-re-mi) and Lydian (major with a raised fourth) scales and only exposed to the Dorian and Phrygian scales, which are both minor, odd. But then again, I’m running it through a modern filter. I also had to keep that in mind when I encountered Richard M. Weaver’s tirade against jazz in his 1948 work Ideas Have Consequences.)

That Plato would consider musical harmony to be as important as other things participants in his dialogues discuss, such as justice or courage, ought to make us consider the place we’ve assigned in our lives to that which our ancestors ascribed the status of the sacred.

Music came along a lot later in human development than sex, obviously, but, either performed or experienced properly, it ought to offer us comparable glimpses into the sublime. And I don’t have narrow parameters. Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos and “Ain’t That Peculiar” by Marvin Gaye qualify as examples of what I mean.

Counterarguments to this position run along the lines of “Isn’t this all a matter of personal taste? Some people like Motown, some like Helen Reddy. A 2020s kid can be quite sincere in asserting that Lana del Ray speaks to her inner being.”

But as technology has democratized both the consumption and the making of music (think playlists and Pro Tools), a pesky little thing that was once central to what music we heard has faded in importance. I’m speaking of standards.

Most people don’t give much thought to applying standards to music. Their relationship with it is much too passive. It’s aural wallpaper that just happens to them, and some of it catches their fancy. Why that is so is not of much importance to them.

When I go into places of business that engage with the public—banks, dentists’ offices, retail establishments—and hear the content being broadcast on the local classic-hits station, I thank God in heaven above that I no longer report to a workplace where I’m subjected to that aural equivalent of Polar Pop all day long.

I get more dismayed than I probably should when I discern, from social media posts, what the music tastes of people whose intellects I admire turn out to be. These are good writers, think tank scholars, and the like, and what turns them on musically leaves me aghast, frankly.

And that is why I feel the current spate of commentary on Taylor Swift, no matter the context or ideological charge, misses the mark.

If we just keep our frame of reference limited to the last century and a quarter—the period in which popular-music genres still with us today developed, as did the above-mentioned celebrity machinery—we see a certain scrappiness in the way musical icons attained that status.

Please help us in our efforts to provide thought-provoking content by offering a donation to The Freemen Foundation.

Think of Duke Ellington and the core of his band, his Washington friends, who had to make two stabs at the New York scene because they’d partied at the expense of making something happen the first time. But they got a label deal, and became the house band at the Cotton Club, owned by English gangster Owney Madden.

Or think of Billie Holliday, who knew her voice was the way out of child prostitution, and cajoled her way into the clubs of Harlem, where she came to the attention of producer John Hammond.

There’s Johnny Cash, a failed appliance salesman who persuaded Sam Phillps of Sun Records to give him a listen while his wife fretted at home with hungry kids and an eviction notice.

The Beatles were, for all intents and purposes, all teenagers when they slogged out eight-hour-a-night sets for merchant marines in the seedy strip clubs of Hamburg’s Reeperbahn, far from parents and other providers of guardrails or rescue.

Swift’s parents, a Merrill Lynch stockbroker and a mutual fund marketing executive, made a point of removing obstacles and finding opportunities for her as soon as she made it clear, at about age 13, that she was determined to be a famous musician. (That she was named after singer-songwriter James Taylor is a strong indication of what her parents considered valuable in the realm of music.)

By the time she was gaining traction, a lot of pop music genres had come to sound alike. Her early hits, such as “Tim McGraw,” “Should Have Said No,” and “You Belong To Me” have the instrumental trappings of country, but the banjos don’t impart a sense of timelessness. The song structures, hooks, vocal delivery, and production values are indistinguishable from the actual pop of the day, or this day, for that matter. They’re indistinguishable from contemporary praise music as well. It’s all the same product, with a slightly different marketing tactic in each case. Her recent work, like “You Need to Calm Down,” is the same bill of fare, with a slight marketing shift.

And her career-long relish for making videos that are vehicles for her personality does no favors to any aspirations she has to be considered an artist and not just an entertainer. Rejoinders along the lines of “everybody’s made videos to go with their recordings since 1980” don’t diminish my case, I would wager.

Much is made of how her core fan demographic resonates with her expression of feelings. I personally have had a bellyful of singer-songwriters giving us ringside seats to their feelings—think the above-mentioned James Taylor—but at least it used to be done with some desire to avoid gimmicks. Swift has made gimmicks one of the principal tools in her box.

Her business acumen comes in for a lot of discussion, and it’s undeniably impressive. But for all the courage involved in standing up to record companies and taking control of her body of work, we are still left with the essential vapidity of that body of work.

We haven’t required any depth from providers of our popular music for many decades. We have simultaneously asked too much and too little of one of our most sublime gifts. Music ought to reflect our imago dei status. What a privilege it is to be able to fashion something so potentially eternity-tapping. That we squander it as we do is reflective of how badly we misunderstand the value of the creation into which we’ve been set down.

Barney Quick is an Adjunct Professor teaching Jazz and Rock & Roll History at Indiana University Columbus. He received his Bachelor’s degree in English and Literature from Wabash College and his Master’s degree in History from Butler University. @Penandguitar

Swift has been ingenious at marketing and branding, but her music is reflective of an era in which very few people write actual melodies any more. Her music is rap music without the punch and the engaging rap-beat. A bit like Hindemith without the avant-garde frisson.

Maybe I'm too old-fashioned, but if I can't recall and whistle the tune of a song, it's not a song. It's just a bunch of notes.

In Swift's case, it's usually only two or three notes repeated over and over, earning her the sobriquet "Two-note Taylor." It sounds like she's a nice and charitable person. So I've been charitable in that characterization.

I liked this very much, although I confess I’m worried that you will say that some bands I like aren’t worth listening to. In your expert opinion, what Rock and Roll bands do you think are good and what bands aren’t?